Commentary

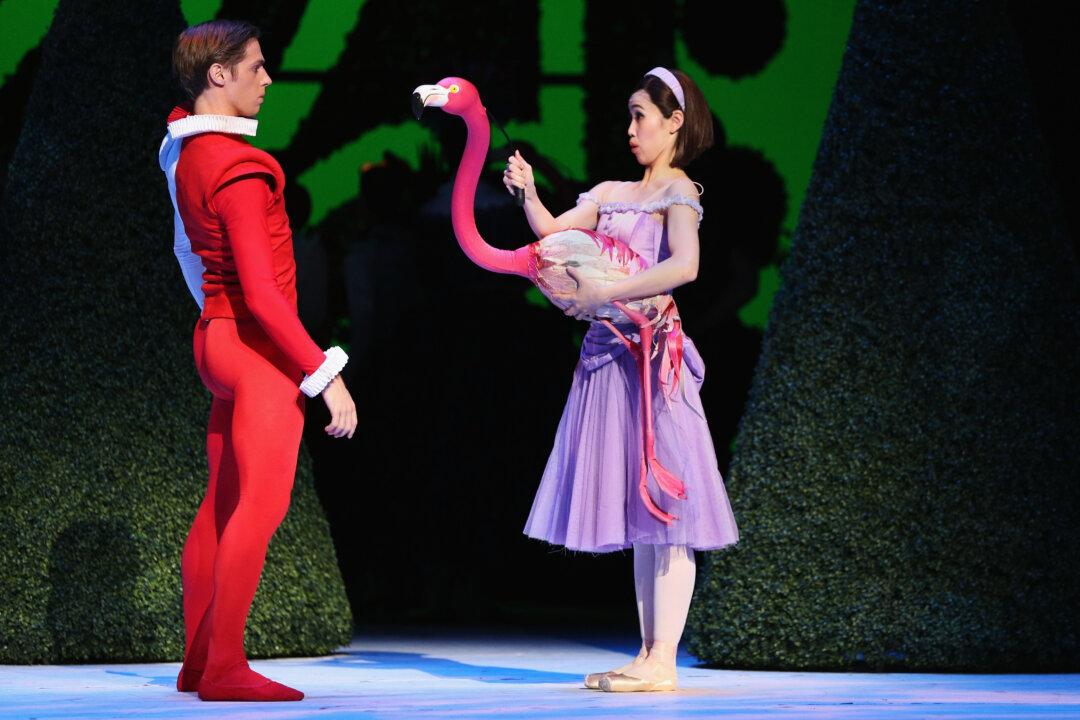

In the modern ballet world, there are only a few choreographers creating new, full-length story ballets in the classical style.

In the modern ballet world, there are only a few choreographers creating new, full-length story ballets in the classical style.