Commentary

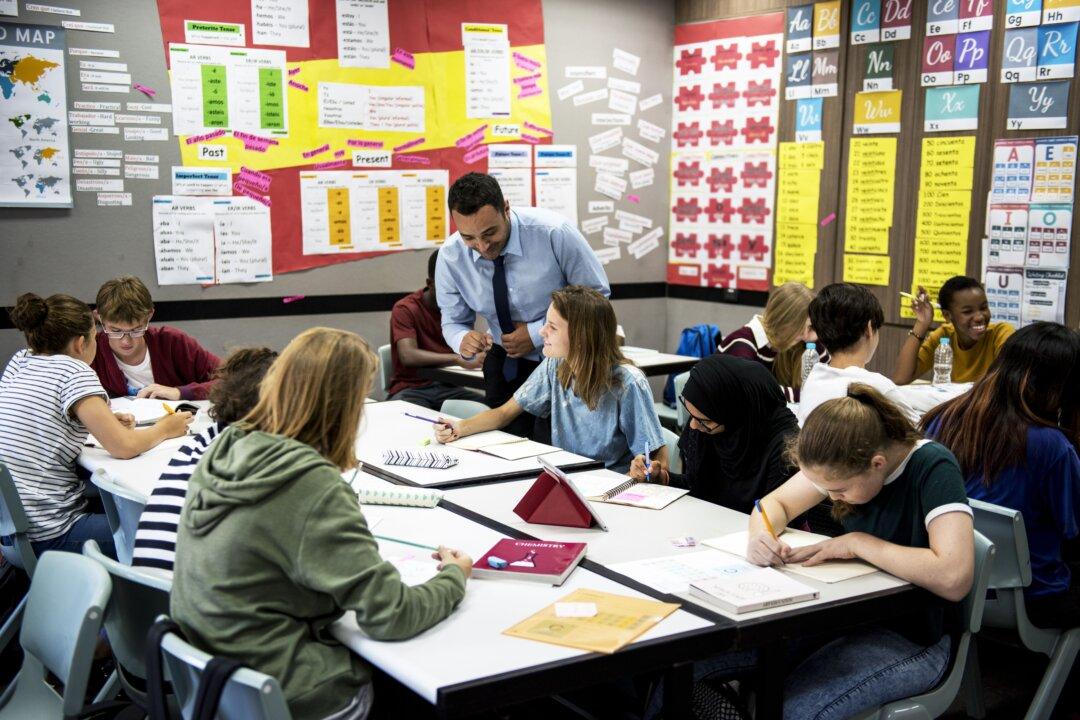

The COVID-19 pandemic is nearly behind us, and it’s about time, too. Hopefully when the school year begins in September, all K-12 students will be back in school on a full-time basis.

The COVID-19 pandemic is nearly behind us, and it’s about time, too. Hopefully when the school year begins in September, all K-12 students will be back in school on a full-time basis.