A leaked document from a major Chinese company with Canadian operations offers evidence that corroborates with security concerns Canada’s intelligence agency has raised over foreign state-owned enterprises.

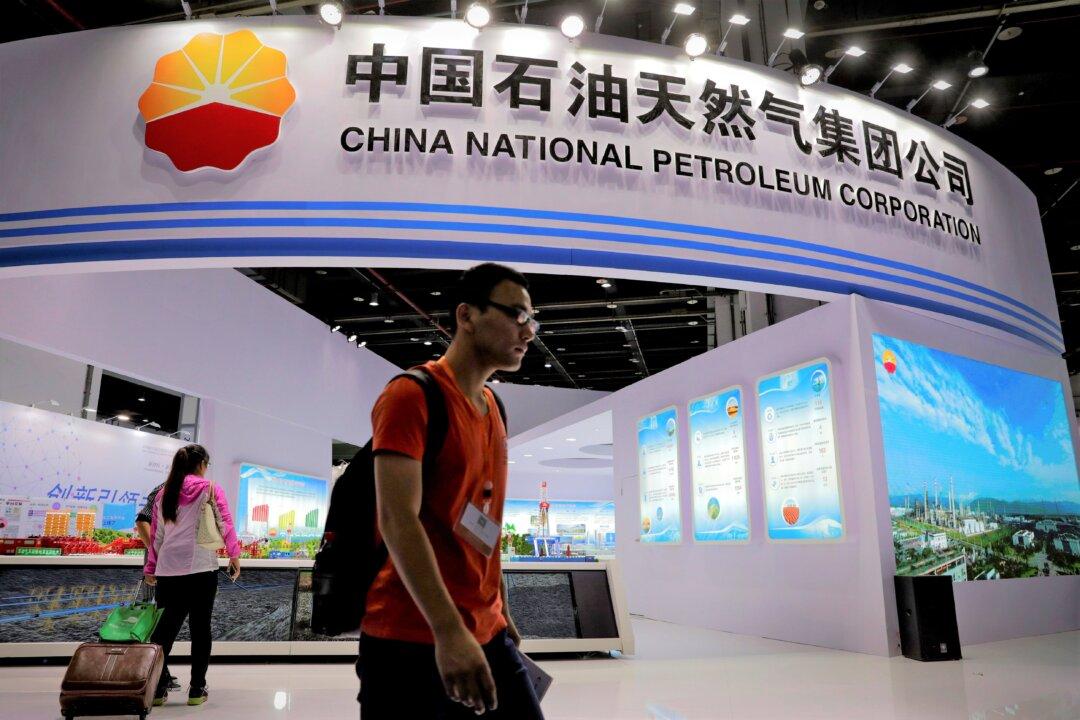

The document, recently obtained by The Epoch Times, is a directive by the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). It was issued in August to its overseas offices in more than 10 countries, including Canada. As previously reported by Epoch, the directive asks the offices to “urgently destroy or transfer sensitive documents” relating to “overseas [Chinese Communist] Party-building activities.”