OTTAWA—Two lawyers representing Sun Qian, a Canadian citizen detained in China, have withdrawn from the case due to pressure from the Chinese authorities, leaving Sun unrepresented since last week.

A Chinese-Canadian businesswoman from Vancouver who became a citizen in 2007, Sun was detained by the Chinese authorities in February 2017 for practising the traditional spiritual discipline Falun Gong, also called Falun Dafa.

As the founder and vice president of Beijing Leadman Biochemistry, Sun travelled regularly between her home in Vancouver and Beijing for work. While at her Beijing residence on Feb. 19, more than 20 plainclothes security agents barged in, ransacked her home, and took her away.

She has since been held at the Beijing First Detention Centre’s 414 Prison Room, a facility notorious for having particularly fierce guards, but is currently without legal representation.

Sun’s family was told to find another lawyer for her, otherwise the Justice Bureau would assign one to her case. But finding a lawyer to defend a Falun Gong practitioner is easier said than done, given the regime’s ongoing persecution campaign against adherents.

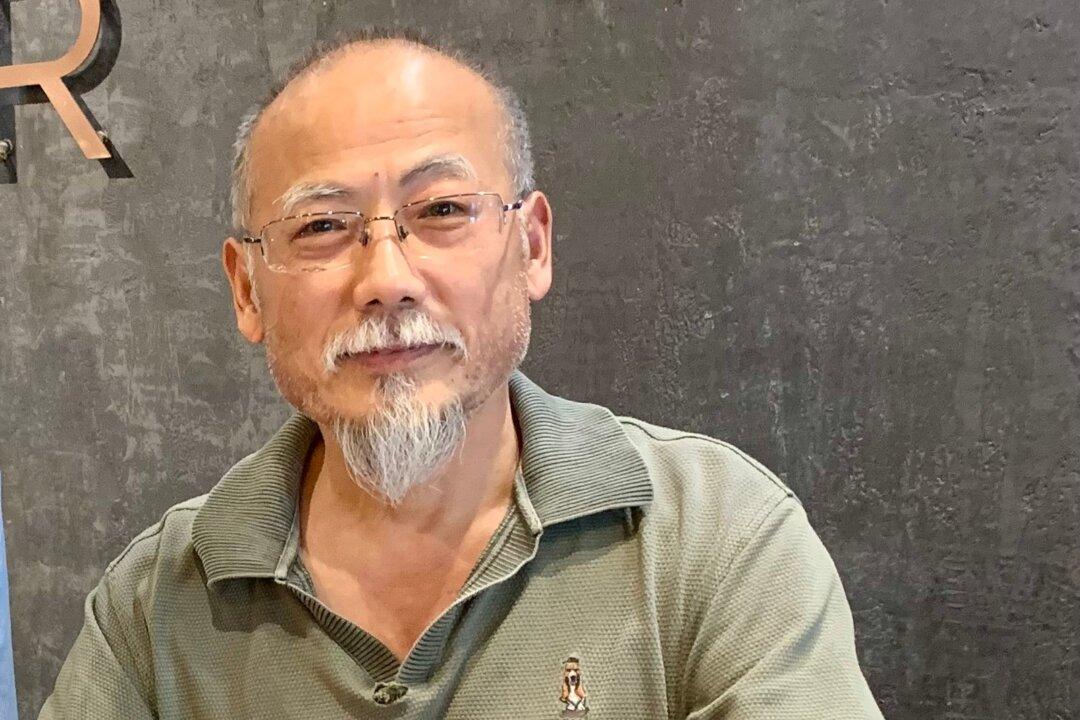

“One of the most dangerous things a lawyer can do is to take on a case on behalf of a Falun Gong practitioner,” said China expert Clive Ansley, a B.C.-based lawyer who lived and practised in China for 14 years.

Ansley said most of the time, legal cases are not brought against Falun Gong practitioners in the first place.

Pressure from all sides

According to Sun’s sister, Sun Zan, lawyers Huang Hanzhong and Xiong Dongmei dropped Sun’s case after being pressured by their law firms’ respective superiors—the justice bureaus at the municipal and provincial levels as well as the Ministry of National Security.Sun Qian’s family learned that in August 2017, officials from various levels of the Justice Bureau had a talk with Huang and asked him not to create any “incidents” or trouble prior to the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which was held in October 2017. They specifically asked him to submit reports to them regarding Sun Qian’s case and another “sensitive” case, which Huang refused to do.

He was again pressured in February around the Chinese New Year, when officials had multiple conversations with him, asking him not to agree to be interviewed by overseas media. They finally ordered him to withdraw from representing Sun Qian and other sensitive cases. Huang pulled out from that point on.

Sun’s family says Xiong experienced similar pressure.

Last August, the law firm Xiong worked at was inspected by the provincial Justice Bureau multiple times. This made the rest of the lawyers in the firm very nervous. Out of fear, the firm’s director opposed Xiong’s filing of a criminal complaint for Sun Qian.

Around the beginning of this year, officials requested Xiong’s brother, sister-in-law, and niece, who lived in another city, travel to Jinan where Xiong lives to talk her into abandoning Sun’s case. By this time, Xiong was becoming worried that the Justice Bureau would revoke her licence to practise law.

Then earlier this month, Sun’s sister said, a judge with last name Li at the Court of the Chaoyang District in Beijing called to inform her that Xiong no longer represents Sun Qian. Li asked the family to find another a lawyer for Sun; otherwise, the Justice Bureau would assign one to her case.

The judge said once a lawyer is found, the case could go to court within a month.

Huang and Xiong took on Sun’s case around June 2017, after her previous lawyer, Glen Gao, was also pressured to withdraw from her case after he made a verbal complaint to the prosecutor at the detention centre about Sun Qian having been tortured by the guards.

Soon after, Gao dropped the case under pressure from his local justice bureau.

Behind the pressure

Aside from the Chinese communist regime’s ongoing campaign of persecution of Falun Gong practitioners, Sun’s family thinks there are other reasons why the Justice Bureau got rid of her lawyers: The criminal complaint they filed resoundingly proves the illegal nature of the persecution.In addition, earlier this year the lawyers filed a criminal complaint against the director of the Beijing Public Security Bureau and the prosecutor responsible for Sun’s case for wrongly using Chinese law in her arrest and detention.

Ansley points out that when the persecution campaign was launched back in 1999, the Chinese Communist Party created a gestapo-like, extra-judicial agency called the 610 Office to handle all matters related to Falun Gong.

“The 610 Office completely replaced the court and the whole judicial process, and the courts themselves were ordered not to accept any lawsuits from Falun Gong practitioners,” he said.

“All lawyers in China were forbidden to take on the defence of Falun Gong.”

According to Yiyang Xia, senior director of policy and research at the Human Rights Law Foundation, it is common for lawyers in China to be disbarred, threatened, and even tortured for attempting to defend Falun Gong practitioners.

Xia added that most lawyers assigned by the Justice Bureau will suggest that their Falun Gong clients plead guilty.

“They are supposed to toe the Communist Party line on the Falun Gong issue. Therefore they will not argue the fundamental issue—that the persecution of Falun Gong is illegal and unconstitutional.”

Yiyang Xia also notes that ultimately, court hearings to sentence Falun Gong practitioners are simply show trials, with the verdict and sentence having been decided before the hearing even takes place.