Commentary

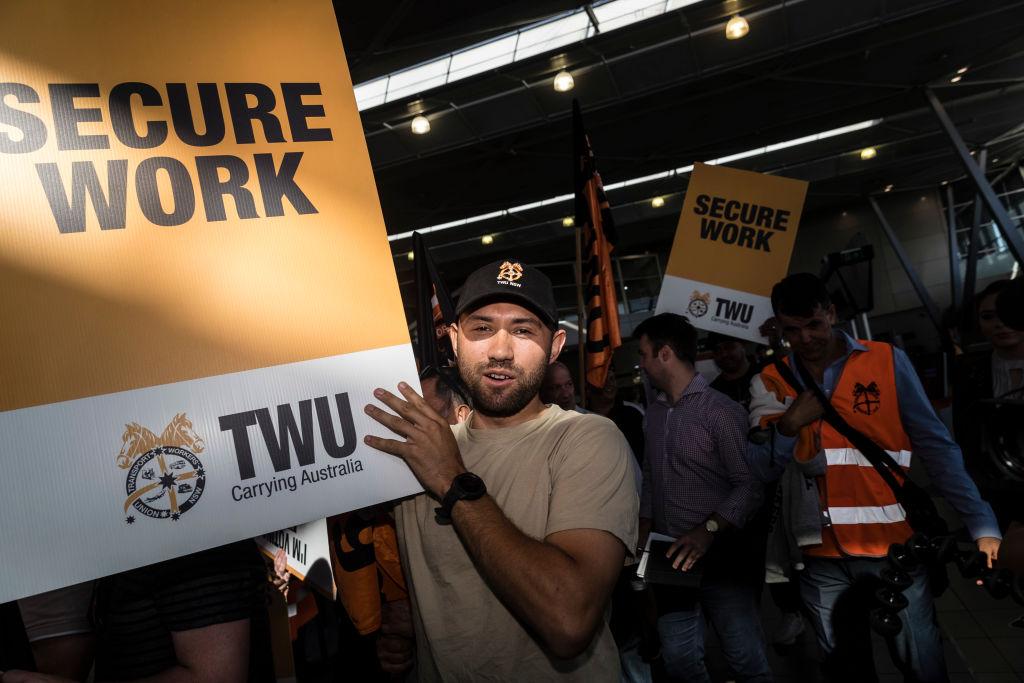

The Australian Labor Party and the trade unions have been waging a war against what they call “insecure work” and contracting for some years, but it is only now they are in power that the reality is starting to dawn on employers.

The Australian Labor Party and the trade unions have been waging a war against what they call “insecure work” and contracting for some years, but it is only now they are in power that the reality is starting to dawn on employers.