CHICAGO—Federal jurors at the biggest gang trial in recent Chicago history on Wednesday convicted the core leadership of the Hobos, who prosecutors billed as an “all-star team” of the type of ruthless gangs police largely blame for an alarming spike in homicides in 2016.

The nation’s third largest city logged 762 homicides last year, the highest tally in 20 years and more in 2016 than the two largest—New York and Los Angeles—combined. More than 50 people were shot and 11 killed over the long Christmas weekend alone as some gangs sought out and shot rivals gathering at holiday parties, police said.

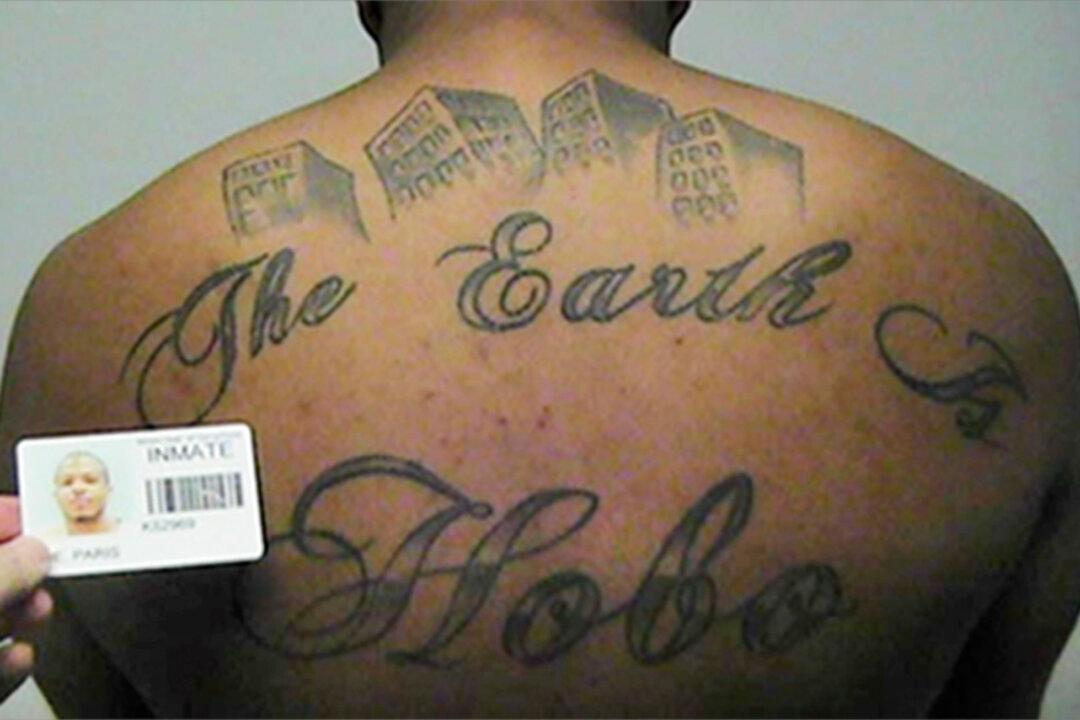

Accused Hobos boss Gregory “Bowlegs” Chester, alleged hitman Paris Poe and four others were found guilty of a racketeering conspiracy. Prosecutors alleged the conspiracy included the murder of at least nine people, from gang rivals to government witnesses. Prosecutors say the Hobos cultivated a reputation for brutality, once even torturing robbery victims with a hot clothing iron, to extend their power on the city’s South Side.

After three months of testimony, 12 panelists deliberated for six days, with notes sent to the judge hinting at some discord inside. The most serious charge in a 10-count indictment was racketeering conspiracy, a charge designed as a legal tool to go after all forms of organized crime. Nine stand-alone counts included drug and gun charges.