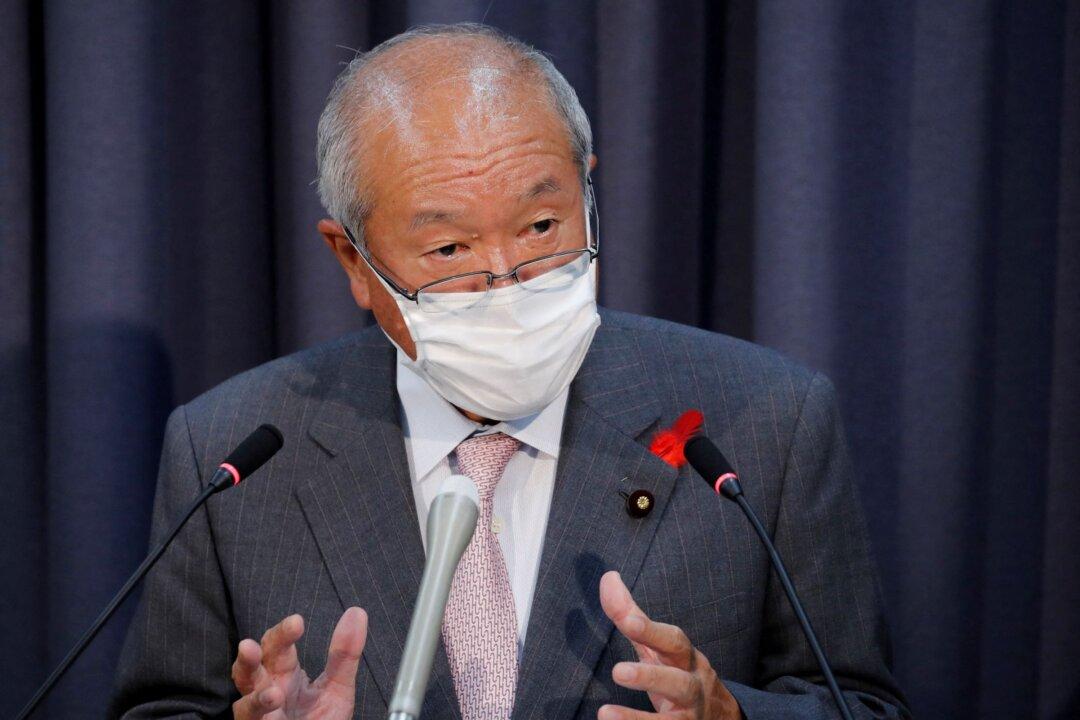

TOKYO–Japan’s Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki stressed on Friday the need for currency stability and said he was watching market moves “carefully,” in the wake of the yen’s recent declines against the dollar.

Domestic media and some market participants have warned of the potential demerits of a weak yen, which pushes up import prices and households’ cost of living at a time when the economy is recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic.