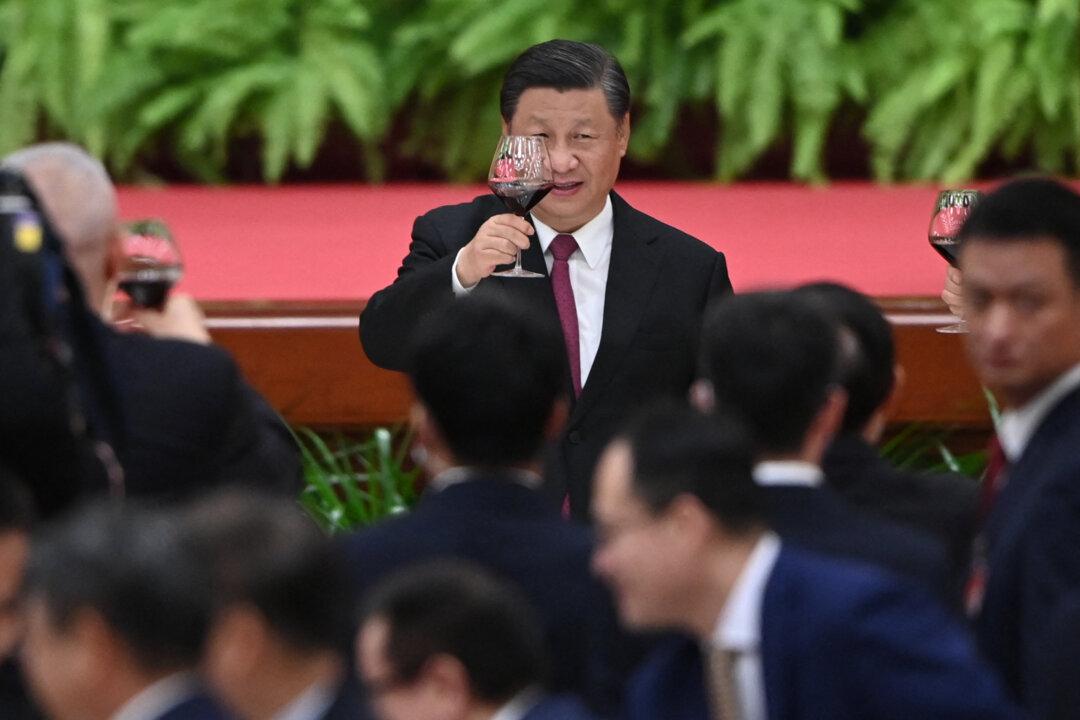

Two recent international phenomena have drawn the world’s attention to Africa. The first is China’s generous financing and the other is the withdrawal of U.S. military forces. What does it mean when the world’s two major powers simultaneously enter and exit the African continent? Why have the countries of Africa become so important to China?

China’s sudden generosity towards African countries is a precautionary measure for the event that it loses part of the U.S. market in the trade war. The actual effectiveness of this strategy may be disappointing, since these countries may not return China’s favors.