Epoch Times: Mr. Sperandeo and Mr. Vieira, you are the two co-authors of “Crash Maker,” an almost 1,500-page-long book, dealing with the Federal Reserve, an unstable financial system and gold. Why don’t we kick off talking about the book for a bit and recap themes still pertinent in today’s market and society.

Victor Sperandeo: This book from 2000 is about a villain and it’s written as a fictional book. The villain is the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. It tries to show in an allegoric form that this position is so powerful; if someone were very intelligent but yet corrupt they could do substantial harm to the citizens of the United States.

This is not the way the Constitution was written. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 is unconstitutional. The monetary system we have is unconstitutional and it is potentially extremely corrupt. That’s the bottom line of the book. It shows how it can be corrupted by the power lust of the chairman of the Fed.

Epoch Times: Mr. Vieira, what do you, as a constitutional lawyer, have to say about the Fed?

Edwin Vieira Jr.: What most people don’t realize is the history of the Federal Reserve goes back really to the beginnings of this country and Alexander Hamilton.

He wanted to combine the big financial interests of the country with the U.S. Treasury so that the big financial interests would be in support of the new government.

That was the basis for his assumption by the new federal government of the state revolutionary war debts. So you had this kind of symbiotic or incestuous relationship set up between bankers and financiers in the private sector on the one hand and U.S. Treasury on the other.

That continued with the First Bank of the United States, which was a private bank chartered by Congress. And then the Second Bank of the United States, which resulted in the famous bank crisis with President Andrew Jackson, where Jackson essentially defeated the bank and the bank lost its charter.

Another one of these incestuous relationships was the National Currency Act, which created the national banking system and is now a part of the Federal Reserve.

All of these national banks trace back to civil war legislation. That system had inherent instability because it is all based on fractional reserves and in that particular case it was tied to the amount of U.S. debt that existed.

At that time the United States government and the people were not interested in expanding the debt, but bankers didn’t like that. So the Federal Reserve System is set up again on this same symbiotic relationship, the Treasury on the one side, the bankers on the other, in order to stabilize the entire system.

Epoch Times: This fractional reserve system was responsible for most of the financial panics in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Mr. Vieira: If you interpreted them correctly, you would see they were tied to the profligacy of the banks but the bankers said:

“Well this is because we don’t have a lender of last resort. If we had someone who could pump in liquidity when we have these panics because the fractional reserve system is collapsing; if we had that kind of system then we could manage the panics. We would never have inflation, we would never have depression.”

All right, the system gets up and running in time for World War l in 1914. But after the end of World War l you have the first depression under the Federal Reserve in 1921–22.

Then comes the banking crisis after the 1929 stock market collapse. In 1931 and 1932, this was the great collapse of the Federal Reserve System.

Roosevelt comes in in 1933, seizes the gold from the American people, turns Federal Reserve notes into legal tender for the first time, and abrogates all of the gold clause contracts that existed—public or private.

Epoch Times: Why is all this unconstitutional?

Mr. Vieira: First, if you look at the currency unit, the Constitution requires the currency unit to be a silver unit, the so-called dollar. That was the Spanish mill dollar; it was adopted by the Continental Congress and it was adopted by Congress after the Constitution was ratified.

And gold was to be also in the system in what I would call bi-metallic system. The unit was silver or gold and was to be measured in silver, but both of them were to circulate side-by-side.

But banks were operating under the fractional reserve principle and generating currency based upon debt and not based on actual gold or silver reserves. This was the inherent instability in the system.

They lent out more currency than they had real money in the vault.

Epoch Times: And once the people wanted to redeem their currency, the banks faced bankruptcy.

Mr. Vieira: That’s right. Then the banks turned to the government and the initial step was what they call suspension of specie payments.

The government said, “Well you don’t have to pay the notes; you don’t have to redeem those currency notes for some period of time while you straighten out your loan portfolio.”

Some of them of course went bust, some of them didn’t. But this was one special instance of the government coming into play here to protect the private bankers.

This was in the 1820s, 1830s, before the U.S. Civil War. Then after the Civil War, the symbiotic relationship had the national banks buy U.S. debt and receive 90 percent of the face value of that debt in currency, which then they could loan out on the fractional reserve principle.

The difficulty in that system was that, at that time, the American people were not willing to tolerate an endless expansion of debt so the bankers weren’t able to increase the amount of currency and loans.

Epoch Times: And the Fed solves that problem for the bankers?

Mr. Vieira: The Federal Reserve solves that problem for them but it still had, in its original formulation, a gold connection.

So they had to get rid of that and they got rid of that on the basis of an emergency that was caused by the failure of the system [The Great Depression].

It’s incredible how people would accept this kind of reasoning.

Now if you ask, ultimately, why it’s unconstitutional, it’s because of that relationship in currency creation.

Congress is supposed to oversee the coinage. The dollar is supposed to be a coin and gold is supposed to circulate in coinage form or in bullion form, not in the credit form; that credit form is tied to the U.S. Treasury.

If you look back historically, the Continental Congress in the War of Independence had the power to, what they call, “emit bills.”

When the Constitution was being discussed, that power was in the draft, the power to borrow money and “emit bills.” They had a debate and struck it out.

Under our constitutional system, the only powers Congress has are the ones given to it by the Constitution. They struck out this provision from the Articles of Confederation, so it logically follows that the power isn’t there. There is no power to create paper currency of the debt-based variety in Congress.

Epoch Times: But you found out there is another reason.

Mr. Vieira: The Federal Reserve is a cartel structure. You have 12 regional banks, and on top of that is the all seeing eye of the pyramid, the board of governors, and the Federal Open Market Committee. Then down below in the pyramid you have all of the private member banks.

Now, if you look at that structure with a constitutional eye, where have I seen this before, is in the structure Roosevelt created in 1933 in his first attempt to overcome the depression.

It was called the National Industrial Recovery Act. They created one of those little pyramids in every major industry—for steal, for coal. They had one for poultry. It was a famous case Schechter v. United States called the “sick chicken case.”

In that industry, legal code was created by the participants, by the private parties. Under that code, a chicken seller could not sell one chicken individually.

He had to sell them in pairs. When the customer says, “Well I don’t like that chicken, it looks sick to me, I only want the one chicken,” and you sold him just one chicken, that was a criminal violation of the code.

This goes up the Supreme Court in the Schechter case and unanimously they declare that structure unconstitutional because it amounted to a delegation of legislative authority to private parties.

That is the exact structure of the Federal Reserve System: it’s a delegation of some kind of monetary authority to private parties, the 12 regional reserve banks.

Of course they do have the board of governors at the top but the National Industrial Recovery Act also had the National Recovery Administration as the little agency on the top overseeing everything.

So why is the Federal Reserve still here? Because its statute was enacted in 1913, and it wasn’t a part of the National Industrial Recovery Act.

Nobody succeeded in bringing a case to the Supreme Court to challenge the Federal Reserve System on the same basis on which the National Industrial Recovery Act was declared unconstitutional.

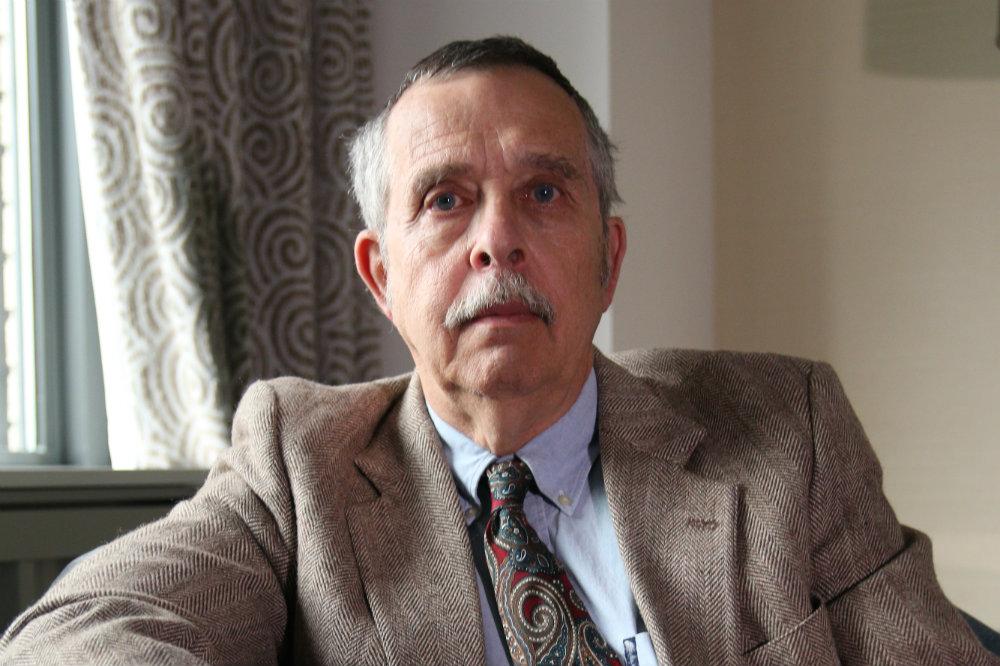

Edwin Vieira Jr., holds four degrees from Harvard: A.B. (Harvard College), A.M. and Ph.D. (Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences), and J.D. (Harvard Law School).

For more than 30 years he has practiced law, with emphasis on constitutional issues. He is also one of our country’s most eminent constitutional attorneys, having brought four cases accepted by the Supreme Court and won three of them.

His two-volume book “Pieces of Eight: The Monetary Powers and Disabilities of the United States Constitution” is the most comprehensive study in existence of American monetary law and history as viewed from a constitutional perspective.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

This is Part 1 in the series with Edwin Vieira Jr. and Victor Sperandeo. Part 1 “Money for Nothing“ may be found here.