Ireland Has Bridging Role Between EU and the Developing World, Says Mrs Robinson

Mrs Mary Robinson, addressed the Institute of International and European Affairs (IIEA) on human rights this week, and spoke to The Epoch Times about climate justice.

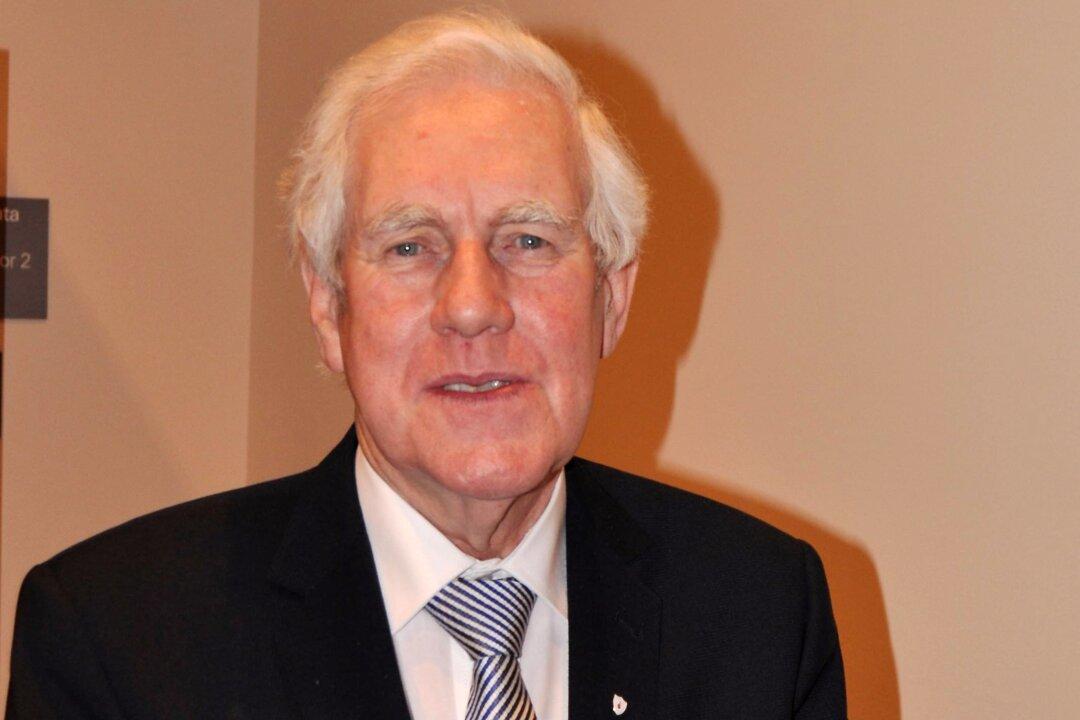

Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mrs Mary Robinson Jung Yeon-Je/getty images

|Updated: