Iran’s supreme leader on Sunday reportedly ordered an amnesty or reduction in prison sentences for “tens of thousands” of people detained amid nationwide anti-government protests shaking the country, acknowledging for the first time the scale of the rebellion.

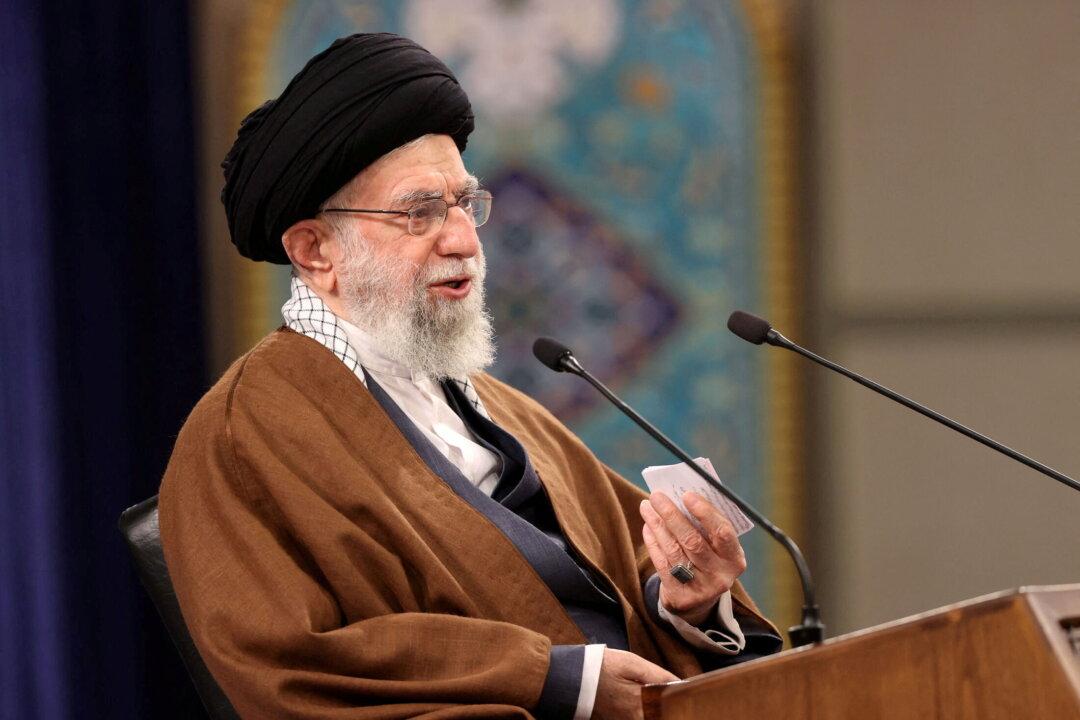

The decree by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, part of a yearly pardoning the supreme leader does before the anniversary of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, comes as authorities have yet to say how many people they detained in the demonstrations. State media also published a list of caveats over the order that would disqualify those with ties abroad or facing spying charges—allegations which have been met with wide international criticism.