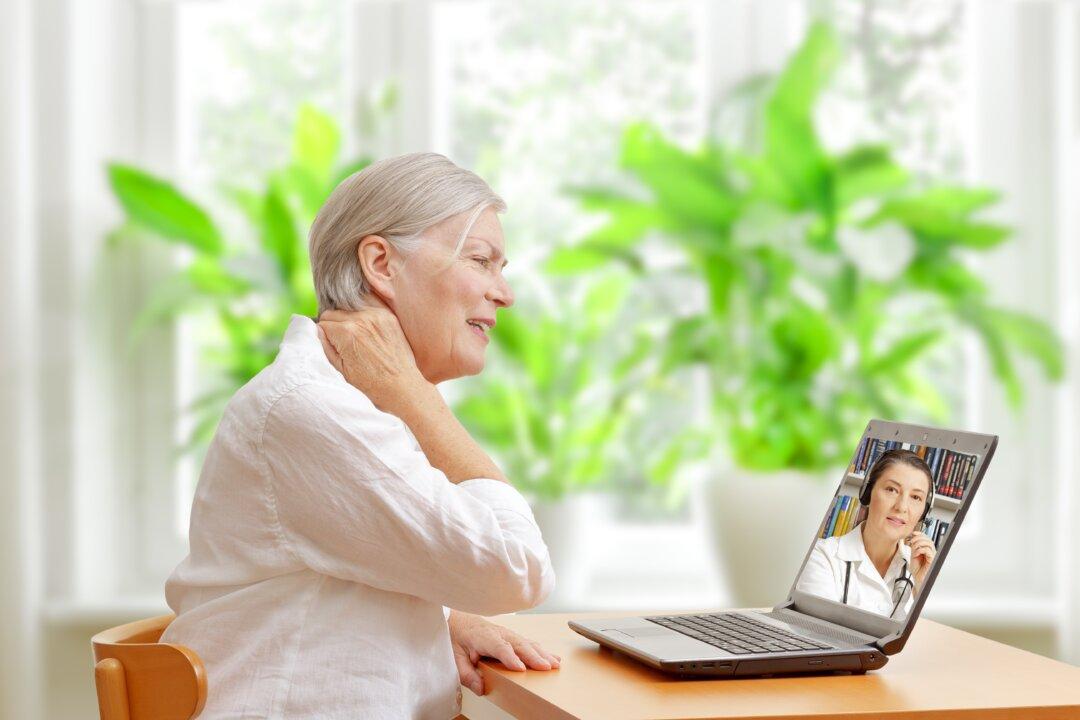

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, people often relied on telemedicine for doctor visits. Now insurers are betting that some patients liked it enough to embrace new types of health coverage that encourage video visits—or that outright insist on them.

Priority Health in Michigan, for example, offers coverage requiring online visits first for nonemergency primary care. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, selling to employers in Connecticut, Maine, and New Hampshire, has a similar plan.