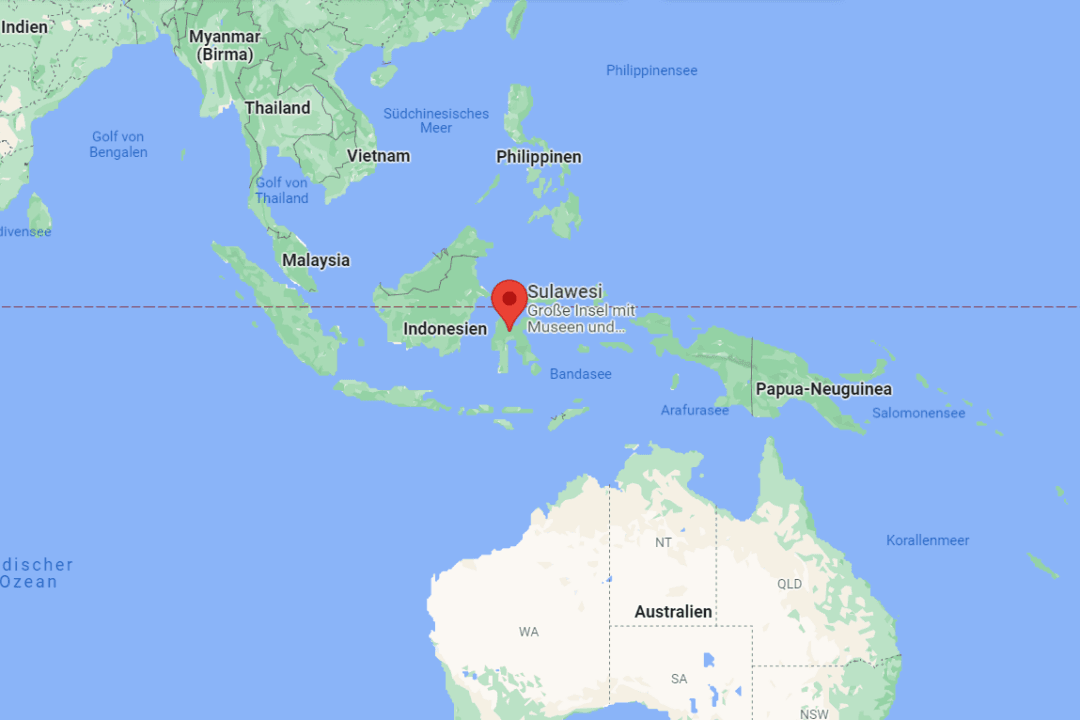

The new Australian government has signalled that it will prioritise deepening ties with the country’s northern neighbour Indonesia.

New Treasurer Jim Chalmers, in an interview with Sky News Afternoon Agenda on May 31, signalled the importance of bilateral ties with Indonesia, noting that Indonesian Treasurer Sri Mulyani was his first international call.