Much of the activism currently tearing Western civilization asunder is driven by ideas that can be traced back to Maoism—a Western interpretation of the writings of Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong—according to several experts on radical movements and strategic theory.

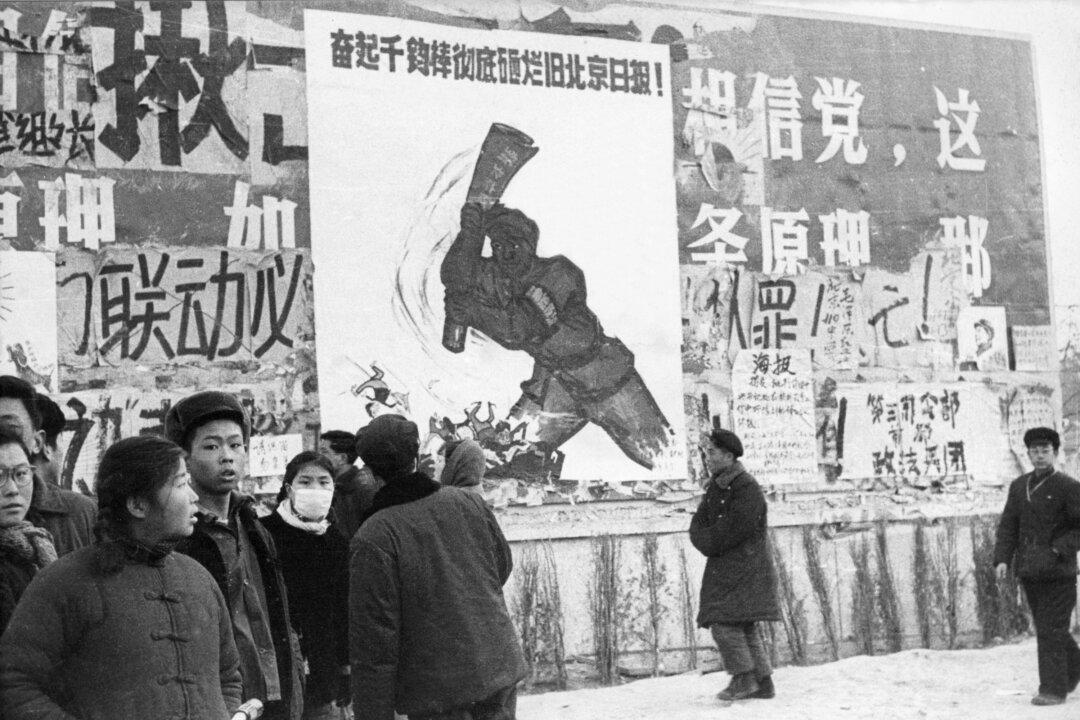

Not only have Mao’s ideas influenced some of the grandfathers of the current activist currents, but also, the tangible results resemble aspects of Chinese communism, inducing his most nightmarish project, the Cultural Revolution, according to David Martin Jones, visiting professor at the War Studies Department, King’s College, London, and M.L.R. Smith, professor of Strategic Theory at the Australian War College, Canberra.