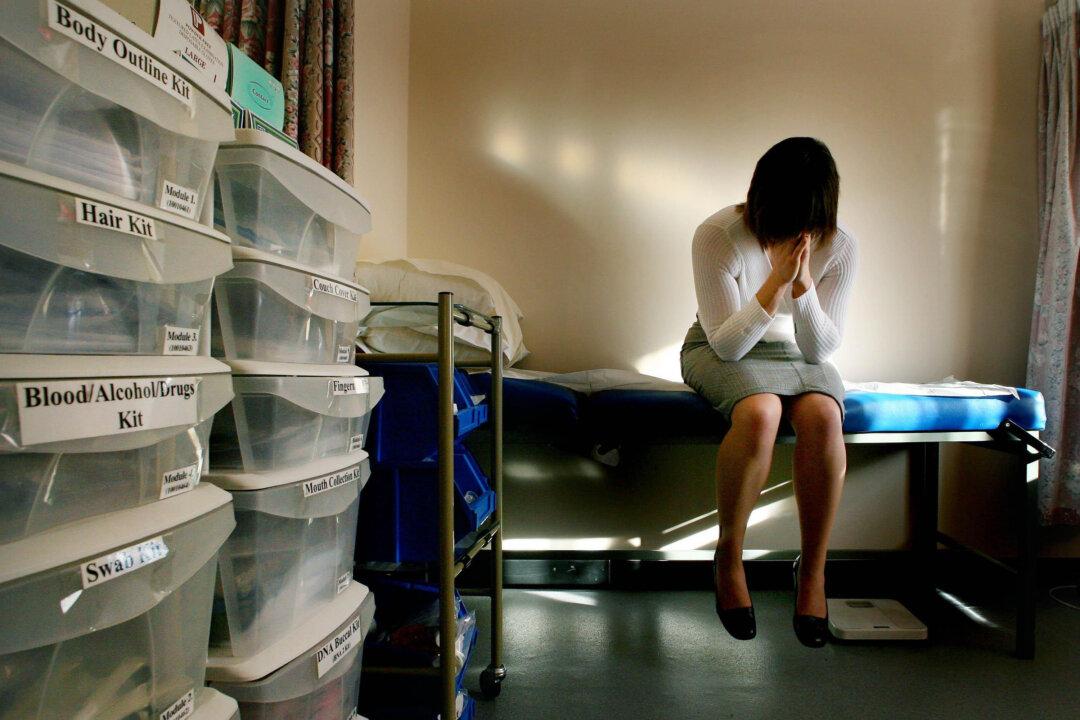

An expert on miscarriages of justice has claimed changes to the law risk undermining the right to a fair trial for men accused of rape and other sexual offences.

The Law Commission is conducting a review of the trial process for prosecutions of rape and other sexual offences in England and Wales—with submissions due by the end of September—while the Scottish government has already proposed piloting juryless trials for rape north of the border.