A new book explains how to help keep your brain in fighting shape throughout your life.

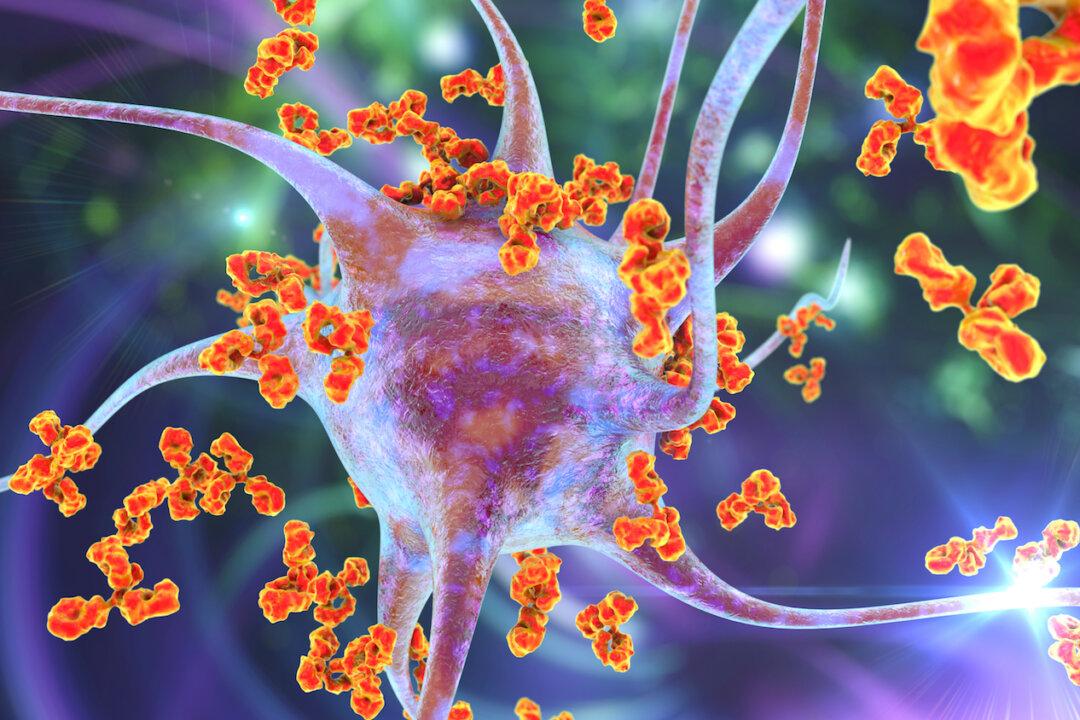

For many people, middle age arrives with some minor mental slip-ups. These “senior moments” are universal experiences that come with aging—and typically harmless. The Centers for Disease Control says one in nine adults ages 45 or older report at least occasional confusion or memory loss.