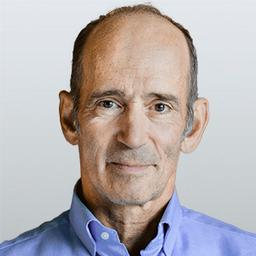

Nutrition and lifestyle expert Ari Whitten has provided a collection of key insights to explain and address low energy levels in his new book, “Eat for Energy: How to Beat Fatigue, Supercharge Your Mitochondria, and Unlock All-Day Energy.”

Whitten also has written an excellent book about infrared light exposure or photobiomodulation as a healing modality, called “The Ultimate Guide to Red Light Therapy: How to Use Red and Near-Infrared Light Therapy for Anti-Aging, Fat Loss, Muscle Gain, Performance, and Brain Optimization.”