Monoclonal antibodies have had their share of ups and downs in the timeline of COVID-19 treatments—but according to news headlines spanning the past two years—not nearly as much as some of the other off-label drugs like ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine. Most of the controversy, if any at all, began at the end of last year, when a handful of preprints written by quite a few scientists said certain brands of monoclonal antibodies would not work for the Omicron variant.

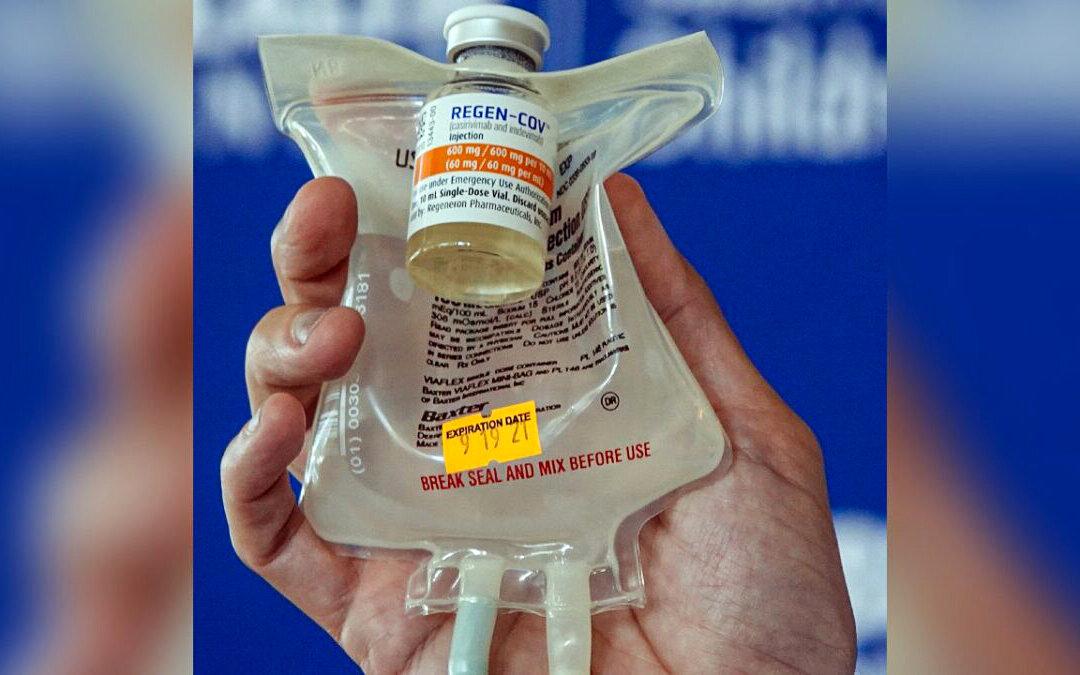

The State of Florida was using sotrovimab—one of the drugs that lost its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in January. Meanwhile companies like Eli Lilly (partnered with AbCellera and AstraZeneca) were poised to benefit with exclusive authorizations. The losers for the U.S. monoclonal markets became Regeneron, who makes REGEN-COV, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) partnered with Vir Biotechnology—the maker of sotrovimab.