WASHINGTON—Our fear of sharks may be able to teach us something about how to manage cybersecurity threats, says Melanie Ensign, security and privacy communications lead at Uber.

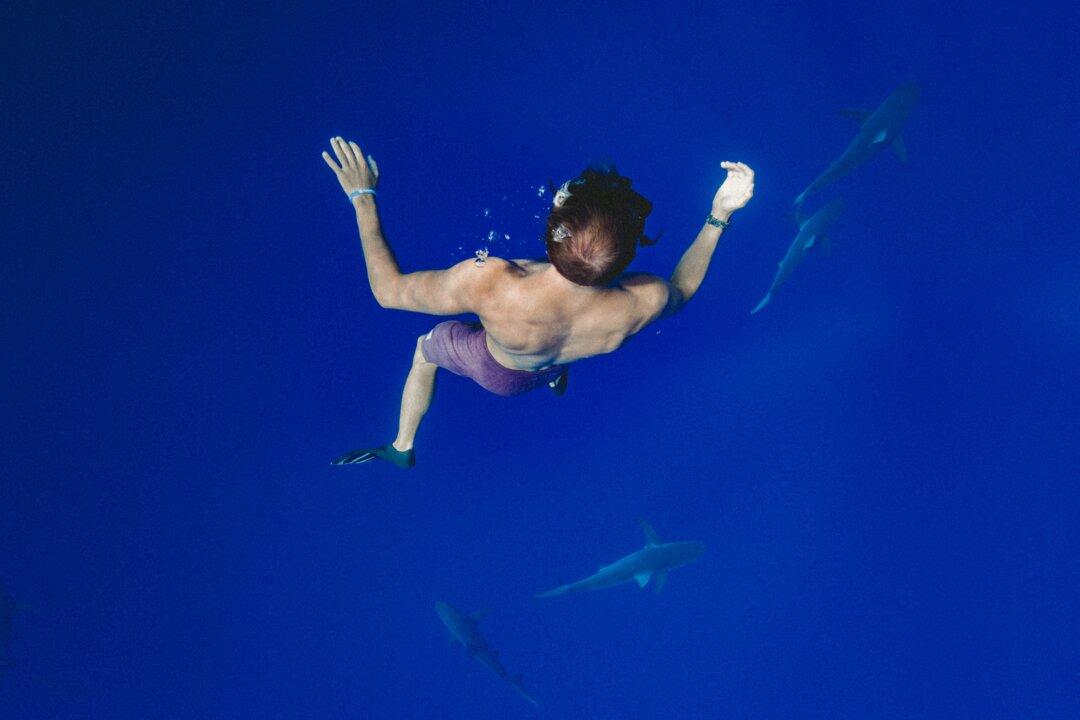

It’s not the shark’s superb hunting skills or ability to kill its prey that is useful, so much as the effect on the human brain. Humans have an irrational fear of sharks, as evidenced by the low chance of ever being attacked by one, compared to the more commonplace occurrence of being in a car crash.