There are a number of studies showing that the partial immunization via available HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines is not only insufficient at reducing overall HPV infection rates but that the vaccines actually cause rarer, more lethal types of HPV to sweep in. The net effect could be devastating increases in HPV-related cancers.

Here I review the biomedical research studies showing that type replacement is real, and that vaccination against the more common types may be, sadly and ironically, expected to cause increases in HPV-related cancer.

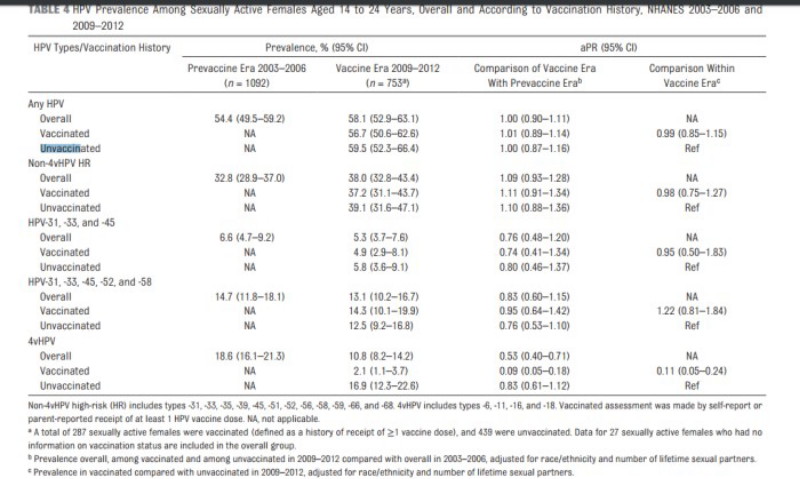

The first study is the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) own study. It looked at HPV prevalence among sexually active females 14 to 24-years-old and showed no net change in HPV infection rate (considering all types) after HPV vaccines were introduced into medical practice:

That study concluded that type replacement did not occur because their univariate analysis of individual types showed no individual type with a significant increase. However, because the vaccines do clear the vaccine-targeted types, the lack of change in overall infection rate shows that type replacement must be occurring.

The second study is from Germany in 2016 by Fisher et al. This study specifically found that high-risk HPV types replaced the vaccine-targeted types. The authros wrote “the percentage of non-vaccine HR-HPV types was higher than expected, considering that eight HPV types formerly classified as ‘low-risk’ or ‘probably high-risk’ are in fact HR-HPV types.”

A third study by Guo et al. published in 2015, compared the prevalence of HPV in vaccinated and non-vaccinated women 20 to 26-years-old. This study also clearly found evidence of type replacement occurring as a result of HPV vaccination:

“The prevalence of high-risk nonvaccine types was higher among vaccinated women than unvaccinated women (52.1 percent vs 40.4 percent, prevalence ratio 1.29, 95 percent CI 1.06–1.57), but this difference was attenuated after adjusting for sexual behavior variables (adjusted prevalence ratio 1.19, 95 percent CI 0.99–1.43). HPV vaccination was effective against all four vaccine types in young women vaccinated after age 12. However, vaccinated women had a higher prevalence of high-risk nonvaccine types, suggesting that they may benefit from newer vaccines covering additional types.”

A fourth study carried out in The Netherlands looked at the clustering of infection by different HPV types in groups with diverse risk factors. Authors Mollers et al. wrote:

“…our findings do suggest that clustering differs among HPV types and varies across risk groups.”

and

“The ecological niche could also be taken through type replacement, which refers to the possibility that elimination of HPV16 and HPV18 could lead to an increased transmission of nonvaccine types. For this to occur, antagonistic interactions are required between vaccine types and those not included in the vaccine (8, 9). Type replacement has been observed following vaccination against other pathogens (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae) (10) and is plausible whenever genotypically diverse pathogen strains compete for the same hosts.”

A study of Italian women also considered type replacement and wrote that “an accurate post-vaccine surveillance is necessary to early detect a possible genotype replacement”