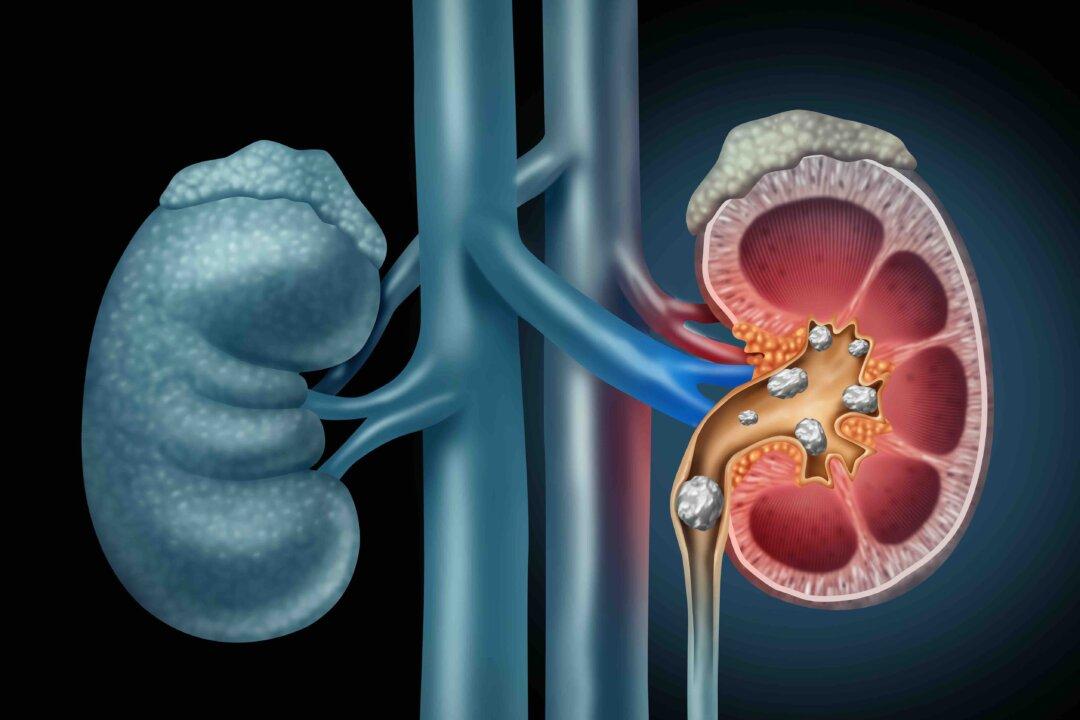

Ultrasound can be used to move, reposition, or break up kidney stones, all while the patient is awake, a new study finds.

The new technique, which combines the use of two ultrasound technologies, may offer an option to move kidney stones out of the ureter with minimal pain and no anesthesia, the researchers reported.