The announcement of the first head transplant has met with skepticism from scientists and stoked fears of Frankenstein’s monster.

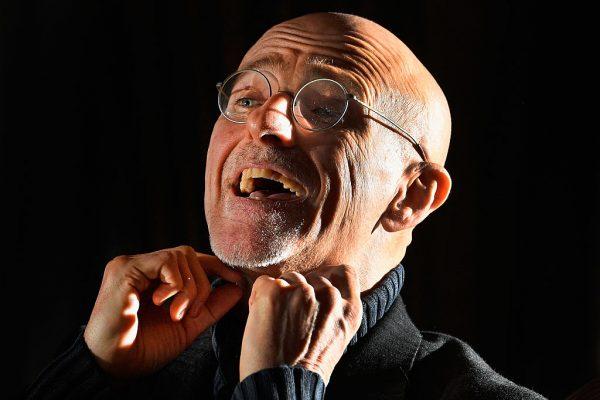

Canavero, who likens himself to Victor Frankenstein, says the experiment is the precursor to the next stage of transplanting between brain-dead subjects. The step after is a full head transplant for a living person.

After Canavero’s research was rejected on ethical grounds in the United States and Europe, it found a home in China with a collaborator, Xiaoping Ren.

“The Americans did not understand,” Canavero told a press conference on Nov. 11.

No Transparency

Professor Karen Rommelfanger is senior editor of the American Journal of Bioethics Neuroscience. She said that given China’s history of using executed prisoners for transplants there are questions that need urgent answering.“What’s very important—that no one has spoken about—is where the bodies are coming from, and who consents.”

“There’s been no response from any of the Chinese collaborators about a very fundamental piece of this whole enterprise—which is consenting individuals to participate.”

She said she is surprised that people have been distracted by the other issues and missed what she sees as the most important issue.

“Everybody has seen the pageantry around the head transplant, and we’ve seen a couple of responses. One is to attack Sergio Canavero himself and just to say what a wacky character he is. The other is to say that this is gross and hard to stomach and to think that this will just go away if we stop looking at it.”

Rommelfanger said that there has been no transparency.

“I’d like to know what the participants were told and what they were they promised. What were the costs and benefits explained to them? I’d like to know what kind of data will be collected along the way.”

“Head transplant” is perhaps more usefully understood as a body transplant—the aim being that when the health of someone’s body fails, they can simply swap it for a healthier, perhaps younger one.

Canavero said he has carried out the procedure twice, which would require four bodies.

The use of the bodies of political prisoners for transplants in China has been well-documented. For decades, China openly admitted to using organs of executed prisoners without consent.

In 2006, investigations revealed that China had a thriving industry harvesting of organs from prisoners of conscience—killed on demand so their organs could be sold for profit.

Research Carries On Despite Objections

The prospect of a head transplant has been raised by Canavero since 2015. Initially, he had a living subject lined up for the first live surgery, who later withdrew.“A full head swap between brain-dead organ donors is the next stage,” he said.

Professor Jan Schnupp, from the University of Oxford, described the proposals as “disturbing.”

Macabre PR for China

Just because news of the research fades away it won’t mean that the experiments have stopped, or the questions have gone away, said Rommelfanger.“I think we won’t hear about this again until they have something positive or a positive spin to report. There will be a lot of failures before we hear anything.”

Rommelfanger said that despite its shortcomings and the stomach-churning potential, this project is acting as a gruesome PR platform for China to ply its no-holds-barred research.

“This is China saying: If you want to do gene editing or make other edgy, perhaps controversial, technological advancement, we’ve got the resources.”