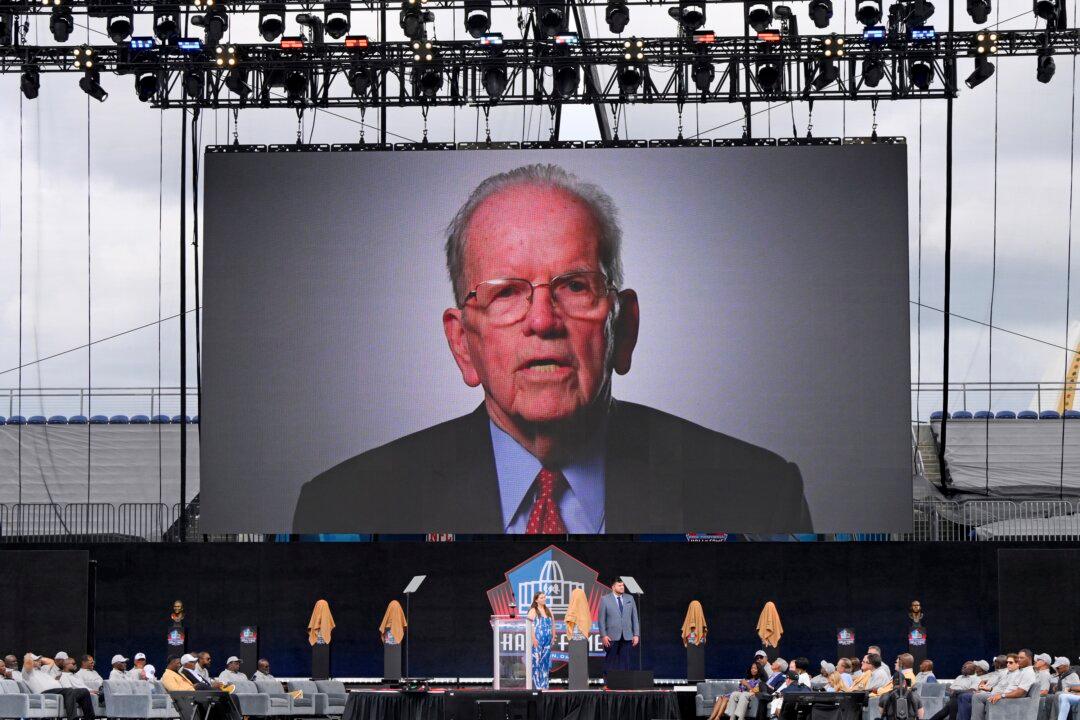

Art McNally, the first on-field official inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, has died. He was 97.

His son, Tom McNally, said Monday that his father died of natural causes at a hospital in Newtown, Pennsylvania, near his longtime home.

Art McNally, the first on-field official inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, has died. He was 97.

His son, Tom McNally, said Monday that his father died of natural causes at a hospital in Newtown, Pennsylvania, near his longtime home.