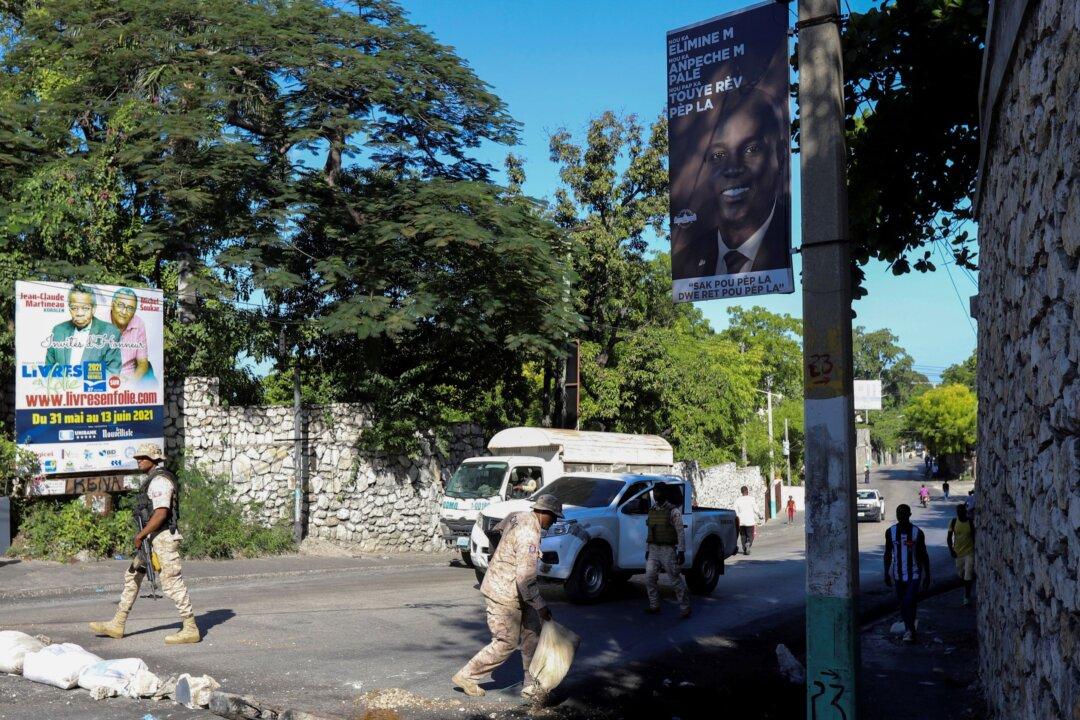

PORT-AU-PRINCE—Haiti’s streets were unusually quiet on Tuesday and gasoline stations remained dry as gangs blocked the entrance to ports that hold fuel stores and the country’s main gang boss demanded that Prime Minister Ariel Henry resign.

Days-long fuel shortages have left Haitians with few transportation options and forced the closure of some businesses. Hospitals, which rely on diesel generators to ensure electricity due to constant blackouts, may shut down as well.