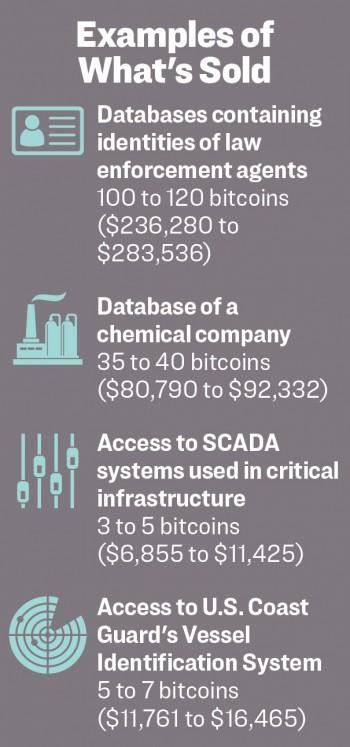

Cyber mercenaries are breaching the systems of governments, financial institutions, critical infrastructure, and businesses, then selling access to them on a marketplace on the darknet, a hidden internet accessible only via specialized software.

All of this is happening on a darknet black marketplace known as the CMarket or “Criminal Market,” formerly known as “Babylon APT.” The marketplace contains a public market, invite-only submarkets, and hacker-for-hire services ready to breach any network in any country.

The Epoch Times was provided with analysis, screenshots, and chat logs from the marketplace by darknet intelligence company BlackOps Cyber. An undercover operative for the company gained access to the marketplace’s invite-only sections and grew close to several of its top members.

According to BlackOps, the site is run by hackers from several countries, who claim to be Latin. However, the main operative, according to the researchers, appears to be a state hacker working for the Chinese Communist Party. The individual runs his operations for the Chinese regime in his day job, and then when operations are finished, he sells the data on companies, governments, and other targets on the black market.