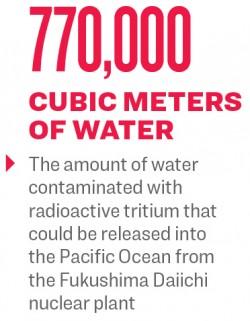

Tokyo Electric Power Company, the operator of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, says it may dump as much as 770,000 cubic meters of water contaminated with the radioactive tritium into the Pacific Ocean, as part of its cleanup efforts following the 2011 tsunami. The announcement has stirred up controversy, yet other, lesser known nuclear facilities around the world have already been releasing tritium into the ocean and the environment.

“After dilution, tritium is released into the ocean, not only from the nuclear power plants but also from the reprocessing plants in the world already,” said nuclear engineer Tadahiro Katsuta of Meiji University, via email.

It is hard to remove tritium from nuclear plant effluent. It is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, and like hydrogen, it can bond with oxygen to make water—tritiated water. Because it is part of the water, it isn’t as easy to remove as other contaminants.

Alternatives to dumping this tritiated water in the ocean include storing it underground or vaporizing it into the atmosphere. But these alternatives have no full-scale research to back them up, nor are they practical with this much tritiated water, said Katsuta.