Former Chinese communist leader Jiang Zemin presided over an extraordinary clampdown on faith groups, particularly the spiritual group Falun Gong, during which the regime deployed tools and tactics that laid the groundwork for the development of China’s modern digital authoritarianism, according to experts and advocates.

Jiang died on Nov. 30 at the age of 96 years in Shanghai, due to leukemia and multiple organ failure, according to Chinese state media.

Meanwhile, advocates and experts have drawn attention to Jiang’s mass human rights violations—atrocities that persist in China today.

Violations

“His biggest demerits: of course the Falun Gong persecution starting 1999 with pogroms, [and] ruling China through corruption and messing around with ethics,” Frank Lehberger, a Europe-based sinologist and analyst of Chinese Communist Party policies, told The Epoch Times in an email.The spiritual practice Falun Gong, which includes meditative exercises and moral teachings focused on the principles, truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance, surged in popularity in the 1990s. Perceiving this to be a threat to his grip on power, Jiang launched an expansive campaign of suppression that resulted in millions of adherents detained for their beliefs.

The former leader’s sweeping oppressive policies thus laid the foundation for other CCP campaigns of repression towards Tibetans, Uyghurs, Mongolians, and those in Hong Kong, noted Lehberger.

Jiang is the first CCP leader to face lawsuits in national as well as international courts.

In 2009, Jiang and four high-ranking CCP officials were indicted at the national Spanish court for committing crimes of genocide and torture against Falun Gong practitioners.

In 2003, three Tibet support groups jointly filed a criminal lawsuit in Spain’s High Court, accusing Jiang and Li Peng, both of whom had retired as China’s president and parliament chief, respectively, of committing genocide and crimes against humanity in Tibet.

Tsering Passang, the founder and chairman of the advocacy group Global Alliance for Tibet and Persecuted Minorities, noted Jiang’s role in crushing the Tibetan Buddhist faith.

“In Tibetan tradition, the Panchen Lama and the Dalai Lama have a vital role of recognizing each other’s reincarnation. Beijing appointed its own Panchen Lama six months later in November 1995. This all happened during the reign of … Jiang Zemin who had absolute authority,” Passang told The Epoch Times over text message.

He added that even the 17th Karmapa, the spiritual head of the 900-year-old Karma Kagyu branch of Tibetan Buddhism, had to dramatically escape from Tibet in 2000 during Jiang’s regime as the spiritual leader was restricted from pursuing his Buddhist education in Tibet.

Lehberger also noted that Jiang ordered the establishment of China’s Great Firewall, the regime’s vast internet censorship and surveillance apparatus. This laid the foundation for the regime’s digital dictatorship, later perfected under the rule of current CCP leader Xi Jinping. It also paved the way for today’s “bio-medical COVID dictatorship,” he said.

Problem with Democracy

French historian and author Claude Arpi relayed accounts of Jiang’s poor comprehension of democracy during his state visits abroad. Hosts had faced problems when rights protestors shouted slogans at the then-leader.“On March 25, 1999, Jiang Zemin was on an official visit to Switzerland. On that day, as he arrived at the parliament in Bern, the Chinese [leader] saw some pro-Tibetan protestors in front of the building with ‘Free Tibet” banners. He got very angry,” said Arpi, now based in India.

“Inside the parliament, he addressed the Swiss lawmakers and said: ‘Today, Switzerland has lost a friend’.”

Arpi mentioned that a few years after this incident, a Swiss diplomat told him that Jiang’s anger continued even during the state banquet with the Swiss president later that evening.

“Jiang Zemin was still so angry that he refused to eat to the great embarrassment of his hosts, who tried to explain what ‘democracy’ was about. In vain!” said Arpi.

Passang participated in protests during Jiang’s state visit to London in 1999, and was detained by the city’s police for over six hours.

“In Cambridge (I did not attend the protest there) the Chinese security/secret service were literally seen directing the British police to contain Tibet protesters,” he said.

“There was no doubt that the policing was beyond reasonable—it was heavy-handed,” he said, adding that the local police later issued apologies for its policing.

Factional Politics

Observers note that Jiang was the leader of a faction within the CCP known as the “Shanghai gang,” in reference to eastern coastal city on which Jiang has a political stranglehold.“A study conducted in 2002 showed how over …12 years (1990-2002), Shanghai received 19.8 billion yuan more in state grants and loans than its chief domestic competitor, the city of Tianjin. This preferential treatment also resulted in more flows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into Shanghai than any other Chinese city,” wrote Shukla, adding that between 1978 and 2002, 86 percent of FDI inflows into China went to the east coast.

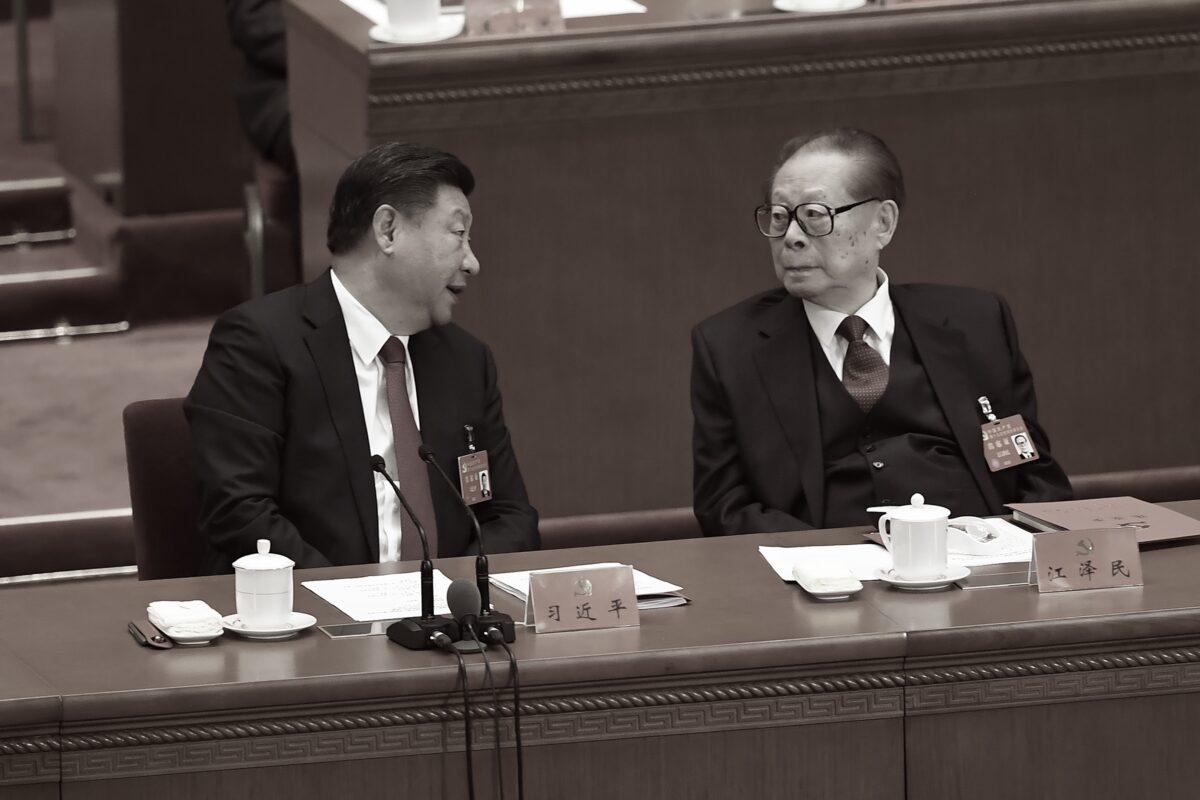

Even after stepping down as leader, Jiang was able to control politics from behind the scenes as a factional head, analysts say.

Lehberger said that Jiang manipulated and hobbled his successor Hu Jintao until 2012, although Jiang had officially retired from all his posts in 2004.

When Xi came to power in 2012, Jiang hoped that his faction could do the same and “manipulate him as some sort of ‘puppet,’” said Lehberger.

Passang noted that Jiang’s death may be good news for Xi.

“His death may be detrimental to his supporter base in the party which means a full opportunity for Xi Jinping,” he said

Lehberger noted that there were rumors in mid-November that Jiang had died, and suggested that Xi had decided to divulge it at a time when historic mass COVID protests were rocking China. But he conceded that there was no way to prove the rumors.

The analyst believes that Xi will now start purging the most influential players left in the Shanghai fraction. “Because it seems Jiang had some sort of tacit agreement on Xi holding still, postponing major persecutions, until Jiang’s death,” said Lehberger.