Focus

Tax inversions

LATEST

Corporations’ Flight to Low-Tax Countries Angers US Voters

U.S. presidential candidates are responding to voters’ ire over a complex tax code that shields the wealthiest from tax payments. Reports of corporate inversions—U.S. firms relocating headquarters to take advantage of lower tax rates in countries like Ireland—highlight the negative consequences of globalization for voters already angry about entrenched income inequality, outsourcing, and job loss. The U.S. Treasury Department has imposed a series of rules to slow the pace of inversions. Farok J. Contractor, a Rutgers Business School professor who researches foreign direct investment, lists the arguments for and against inversions. “There is an inherent contradiction, as well as jurisdictional disputes, in a world with separate country-by-country taxation while multinationals treat the world as one economic space,” he concludes. Estimates suggest the U.S. tax burden is near the average of OECD economies, but the country’s persistent reputation for high taxes and inefficient government may hurt prospects for foreign investment.

|

Protect American Companies by Reforming Corporate Tax

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady (R-Texas) hosted a hearing last month exploring how to reform the U.S. corporate tax system.

|

Mega Merger of Botox and Viagra Makers Sets Off Alarm in US Treasury

Viagra maker Pfizer and Botox maker Allergan agree to merge in a roughly $160 billion deal, few days after Treasury tightened the rules on tax inversion.

|

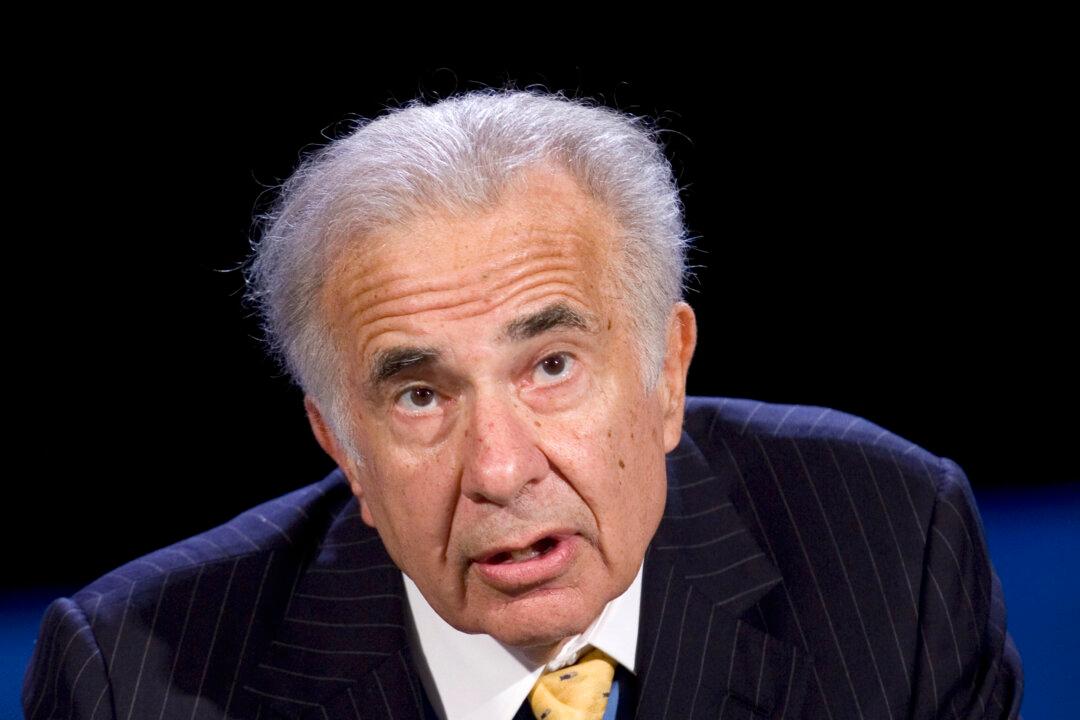

Billionaire Starts Super PAC to Push Corporate Tax Revamp

Billionaire New York investor Carl Icahn said Wednesday he is creating a $150 million super PAC focused on revising corporate tax law.

|

Rather Than Worry About Tax ‘Inversions,’ President Obama and Congress Should Fix the Tax System

Washington has a new corporate scourge: tax “inversions,” through which an American company sells itself to or merges with a foreign firm so that it can avoid paying full U.S. taxes. There’s an easy way to thwart these moves: Cut corporate tax rates and pay for the rate cut by eliminating some of the country’s biggest tax breaks.

|

Corporations’ Flight to Low-Tax Countries Angers US Voters

U.S. presidential candidates are responding to voters’ ire over a complex tax code that shields the wealthiest from tax payments. Reports of corporate inversions—U.S. firms relocating headquarters to take advantage of lower tax rates in countries like Ireland—highlight the negative consequences of globalization for voters already angry about entrenched income inequality, outsourcing, and job loss. The U.S. Treasury Department has imposed a series of rules to slow the pace of inversions. Farok J. Contractor, a Rutgers Business School professor who researches foreign direct investment, lists the arguments for and against inversions. “There is an inherent contradiction, as well as jurisdictional disputes, in a world with separate country-by-country taxation while multinationals treat the world as one economic space,” he concludes. Estimates suggest the U.S. tax burden is near the average of OECD economies, but the country’s persistent reputation for high taxes and inefficient government may hurt prospects for foreign investment.

|

Protect American Companies by Reforming Corporate Tax

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady (R-Texas) hosted a hearing last month exploring how to reform the U.S. corporate tax system.

|

Mega Merger of Botox and Viagra Makers Sets Off Alarm in US Treasury

Viagra maker Pfizer and Botox maker Allergan agree to merge in a roughly $160 billion deal, few days after Treasury tightened the rules on tax inversion.

|

Billionaire Starts Super PAC to Push Corporate Tax Revamp

Billionaire New York investor Carl Icahn said Wednesday he is creating a $150 million super PAC focused on revising corporate tax law.

|

Rather Than Worry About Tax ‘Inversions,’ President Obama and Congress Should Fix the Tax System

Washington has a new corporate scourge: tax “inversions,” through which an American company sells itself to or merges with a foreign firm so that it can avoid paying full U.S. taxes. There’s an easy way to thwart these moves: Cut corporate tax rates and pay for the rate cut by eliminating some of the country’s biggest tax breaks.

|