Focus

Muslim Brotherhood

LATEST

How a Tiny Gulf Nation Is Waging a Massive Information War on the West: Jonathan Schanzer

Dr. Jonathan Schanzer is Senior Vice President at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and author of several books on Islamic extremism.

|

March of Arab Spring on Pause

The Arab Spring, a wave of protests sweeping through the Middle East in 2011, inspired hope for more freedoms in the region. Such anticipation was short-lived as authoritarian rulers recalibrated strategies for control by strengthening alliances with constituencies including elites, secular middle classes and workers who are wary of rapid changes that might threaten economic stability, explains Hicham Alaoui, the director of the non-profit Hicham Alaoui Foundation for Social Science Research. He delivered the annual Coca-Cola World Fund at Yale Lecture this year, and this essay is based on that lecture. He describes operational tactics employed by some governments: repression of opposition and extensive monitoring of public activities, exploitation of fear, selective enforcement of strict interpretations for Islam, and increased interventions throughout the region. “However, at the heart of retrenched authoritarianism rests a long-term gamble,” notes Alaoui, that “all else being equal, youth activists that comprise the vanguard of opposition movements can be permanently deactivated.” Societies with a high proportion of youth cannot ignore that driving force of change.

|

Egypt Warns Against Unrest on Uprising Anniversary

Egypt’s president, speaking ahead of next week’s anniversary of the 2011 uprising that toppled longtime ruler Hosni Mubarak, vowed on Saturday to unleash a firm response to any unrest and to press ahead with the fight against Islamic militants.

|

Egypt Rights Group Visits Prison, but Says Access Lacking

Egypt’s state-sanctioned human rights body said a delegation was able to visit a prison holding Muslim Brotherhood leaders on Tuesday but that authorities sharply limited access to prisoners.

|

Why the Sinai Peninsula Is so Dangerous—And Why the Rest of Us Should Care

While the cause of the Russian airliner crash in Egypt remains unknown, the incident has re-focused the world’s attention on the Sinai Peninsula.

|

Journalists Face Threat of Terror Charges for Reporting

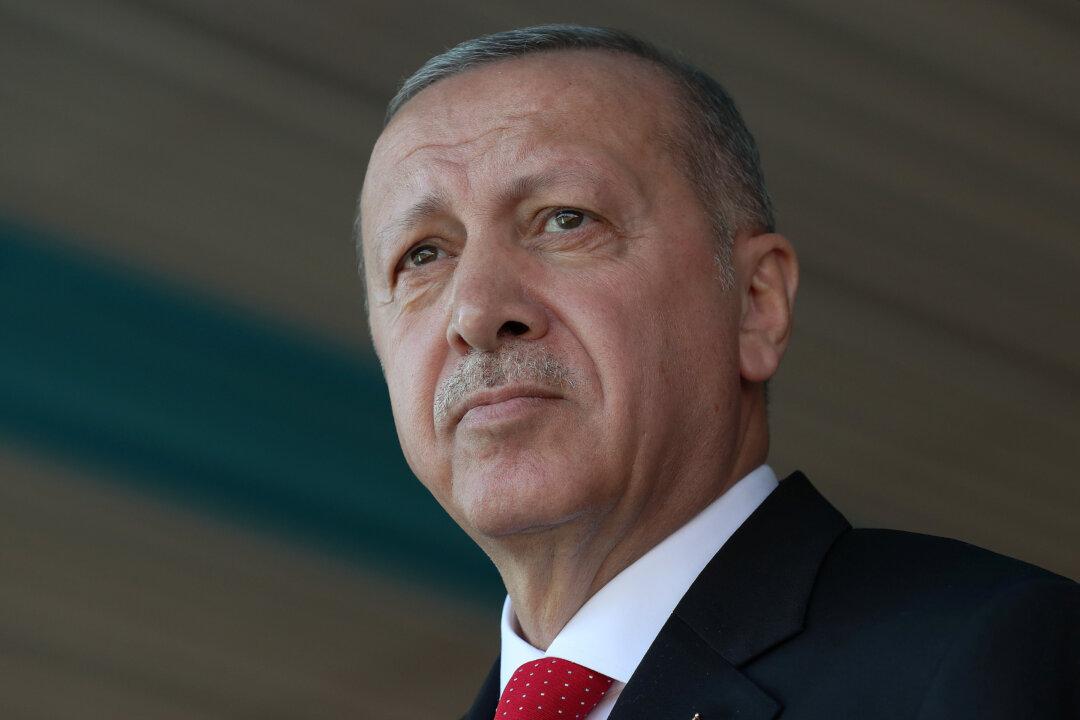

The detention of three Vice News journalists in Turkey last month came with all-too-familiar charges of terror-related crime

|

Clashes at Islamist March in Egyptian Capital Kill 5

Egyptian security forces and Muslim Brotherhood supporters traded gunfire that killed at least five people after clashes erupted during a Friday demonstration in Cairo

|

How a Tiny Gulf Nation Is Waging a Massive Information War on the West: Jonathan Schanzer

Dr. Jonathan Schanzer is Senior Vice President at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and author of several books on Islamic extremism.

|

March of Arab Spring on Pause

The Arab Spring, a wave of protests sweeping through the Middle East in 2011, inspired hope for more freedoms in the region. Such anticipation was short-lived as authoritarian rulers recalibrated strategies for control by strengthening alliances with constituencies including elites, secular middle classes and workers who are wary of rapid changes that might threaten economic stability, explains Hicham Alaoui, the director of the non-profit Hicham Alaoui Foundation for Social Science Research. He delivered the annual Coca-Cola World Fund at Yale Lecture this year, and this essay is based on that lecture. He describes operational tactics employed by some governments: repression of opposition and extensive monitoring of public activities, exploitation of fear, selective enforcement of strict interpretations for Islam, and increased interventions throughout the region. “However, at the heart of retrenched authoritarianism rests a long-term gamble,” notes Alaoui, that “all else being equal, youth activists that comprise the vanguard of opposition movements can be permanently deactivated.” Societies with a high proportion of youth cannot ignore that driving force of change.

|

Egypt Warns Against Unrest on Uprising Anniversary

Egypt’s president, speaking ahead of next week’s anniversary of the 2011 uprising that toppled longtime ruler Hosni Mubarak, vowed on Saturday to unleash a firm response to any unrest and to press ahead with the fight against Islamic militants.

|

Egypt Rights Group Visits Prison, but Says Access Lacking

Egypt’s state-sanctioned human rights body said a delegation was able to visit a prison holding Muslim Brotherhood leaders on Tuesday but that authorities sharply limited access to prisoners.

|

Why the Sinai Peninsula Is so Dangerous—And Why the Rest of Us Should Care

While the cause of the Russian airliner crash in Egypt remains unknown, the incident has re-focused the world’s attention on the Sinai Peninsula.

|

Journalists Face Threat of Terror Charges for Reporting

The detention of three Vice News journalists in Turkey last month came with all-too-familiar charges of terror-related crime

|

Clashes at Islamist March in Egyptian Capital Kill 5

Egyptian security forces and Muslim Brotherhood supporters traded gunfire that killed at least five people after clashes erupted during a Friday demonstration in Cairo

|