Focus

Labor Camp

LATEST

He Escaped From a North Korean Prison Camp—Now He’s Showing the World His Torture Scars

In an exclusive interview, human rights activist Shin Dong-hyuk shows scars that he suffered from torture inside a North Korean prison camp.

|

Meet the Only Physician Who Escaped a Khmer Rouge Death Camp

A doctor who witnessed the genocide of the Cambodian people tells his story to Epoch Times.

|

Heartrending Letters From Soviet-Era Siberian GULAGs

Banned from writing to loved ones, and only allowed letters from family members twice a year, prisoners in Soviet labor camps came up with many ways to squirrel out messages. With no pencils, papers or envelopes, they were forced to write on cigarette boxes, scratch out words on tree bark, or embroider messages with fish bone on tissues.

|

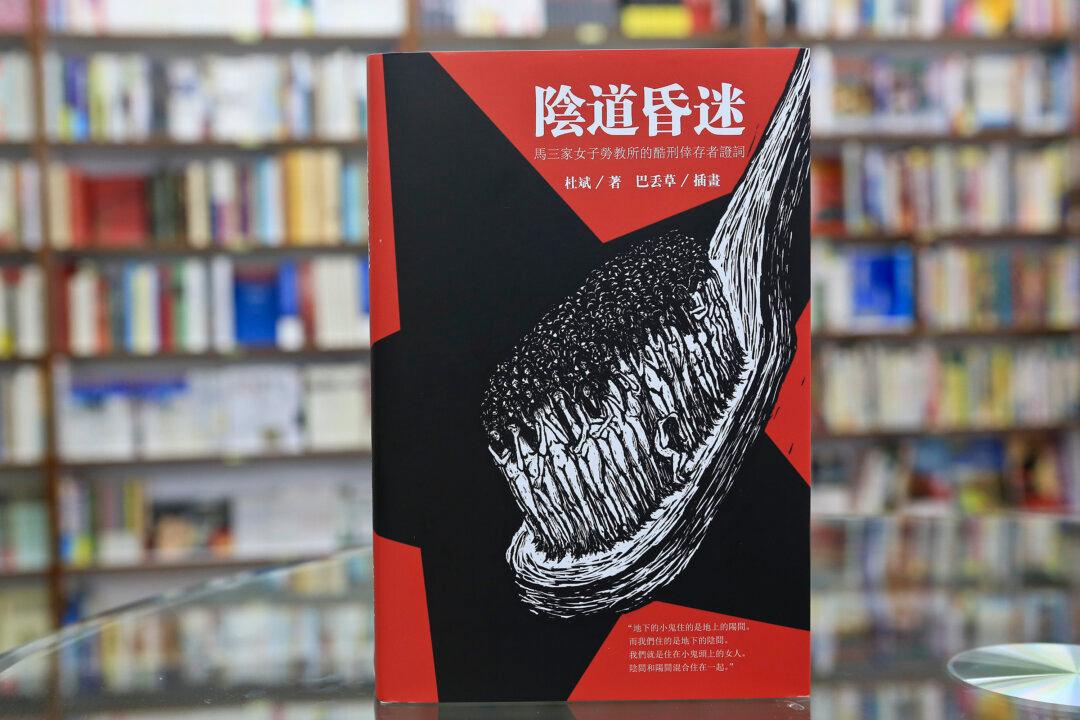

New Book Exposes Sexual Torture in Masanjia Labor Camp

“Vaginal Coma,” book by photojournalist Du Bin, was published, revealing the brutal sex torture to female inmates in Masanjia Women’s Labor Camp

|

Courage Challenges Regime of Illegality in China

Seeking justice in China requires being willing to pit weak flesh and blood against the steel of oppression. Four human rights lawyers who took that risk at a remote spot in the far north of China have focused the nation’s attention on the secret, extra-legal hellholes used to terrorize the faithful, the dissident, and the unlucky in China.

|

Lawyers in China Voice Skepticism About RTL Reform

A group of human rights lawyers stated skepticism about China’s abolishment of re-education through labor.

|

The Darkness of China’s Legal System Exposed

Two reports that came out in early April this year have once again exposed the darkness of China’s legal system, which heedlessly takes away people’s lives and has no limits in how it debases human dignity.

|

Masanjia Victims’ Journey of Protest Continues

Masanjia Labor Camp victims protested a government report denying torture in the camp, while the May issue of Lens magazine was delayed after it published a report about abuses in Masanjia.

|

State Media Dodges Torture Victims

A group of female Masanjia torture victims have confronted Xinhua, the official Chinese mouthpiece, over its publication of a torture denial report issued by Liaoning officials.

|

Harrowing Documentary About Slavery and Torture in China Released

A documentary about the extraordinary torture and abuse meted out at the Chinese labor camp Masanjia, in Liaoning Province, has been published.

|

Sister in Washington Appeals for Sister in Torture Den

Ma Chunmei, a resident of the Washington metro area, is trying by every means to rescue from the Masanjia labor camp her sister, Ma Chunling, who has been there since August 2012. She fears the worst.

|

Tabbed for Organ Harvesting at Masanjia

Sometimes practitioners of Falun Gong would disappear from Masanjia Women’s Forced Labor Camp without a trace. Their clothes and other belongings would remain behind, but the practitioners could not be found. One inmate only fully understood what those disappearances meant after she had been released from the labor camp.

|

‘Women Above Ghost’s Head'

A new documentary reveals the torture experienced by Chinese women detained at Masanjia labor camp.

|

Chinese Regime Labor Camp Reforms Bring Panic, Puzzlement, Hope

The new Chinese leadership has announced that it’s going to scrap the system of “re-education through forced labor”—and both officials and dissidents are still trying to figure out what it means.

|

He Escaped From a North Korean Prison Camp—Now He’s Showing the World His Torture Scars

In an exclusive interview, human rights activist Shin Dong-hyuk shows scars that he suffered from torture inside a North Korean prison camp.

|

Meet the Only Physician Who Escaped a Khmer Rouge Death Camp

A doctor who witnessed the genocide of the Cambodian people tells his story to Epoch Times.

|

Heartrending Letters From Soviet-Era Siberian GULAGs

Banned from writing to loved ones, and only allowed letters from family members twice a year, prisoners in Soviet labor camps came up with many ways to squirrel out messages. With no pencils, papers or envelopes, they were forced to write on cigarette boxes, scratch out words on tree bark, or embroider messages with fish bone on tissues.

|

New Book Exposes Sexual Torture in Masanjia Labor Camp

“Vaginal Coma,” book by photojournalist Du Bin, was published, revealing the brutal sex torture to female inmates in Masanjia Women’s Labor Camp

|

Courage Challenges Regime of Illegality in China

Seeking justice in China requires being willing to pit weak flesh and blood against the steel of oppression. Four human rights lawyers who took that risk at a remote spot in the far north of China have focused the nation’s attention on the secret, extra-legal hellholes used to terrorize the faithful, the dissident, and the unlucky in China.

|

Lawyers in China Voice Skepticism About RTL Reform

A group of human rights lawyers stated skepticism about China’s abolishment of re-education through labor.

|

The Darkness of China’s Legal System Exposed

Two reports that came out in early April this year have once again exposed the darkness of China’s legal system, which heedlessly takes away people’s lives and has no limits in how it debases human dignity.

|

Masanjia Victims’ Journey of Protest Continues

Masanjia Labor Camp victims protested a government report denying torture in the camp, while the May issue of Lens magazine was delayed after it published a report about abuses in Masanjia.

|

State Media Dodges Torture Victims

A group of female Masanjia torture victims have confronted Xinhua, the official Chinese mouthpiece, over its publication of a torture denial report issued by Liaoning officials.

|

Harrowing Documentary About Slavery and Torture in China Released

A documentary about the extraordinary torture and abuse meted out at the Chinese labor camp Masanjia, in Liaoning Province, has been published.

|

Sister in Washington Appeals for Sister in Torture Den

Ma Chunmei, a resident of the Washington metro area, is trying by every means to rescue from the Masanjia labor camp her sister, Ma Chunling, who has been there since August 2012. She fears the worst.

|

Tabbed for Organ Harvesting at Masanjia

Sometimes practitioners of Falun Gong would disappear from Masanjia Women’s Forced Labor Camp without a trace. Their clothes and other belongings would remain behind, but the practitioners could not be found. One inmate only fully understood what those disappearances meant after she had been released from the labor camp.

|

‘Women Above Ghost’s Head'

A new documentary reveals the torture experienced by Chinese women detained at Masanjia labor camp.

|

Chinese Regime Labor Camp Reforms Bring Panic, Puzzlement, Hope

The new Chinese leadership has announced that it’s going to scrap the system of “re-education through forced labor”—and both officials and dissidents are still trying to figure out what it means.

|