Focus

exoplanet

LATEST

NASA Announces 7 New Planets (Video)

Scientists confirmed the existence of seven new planets orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1.

|

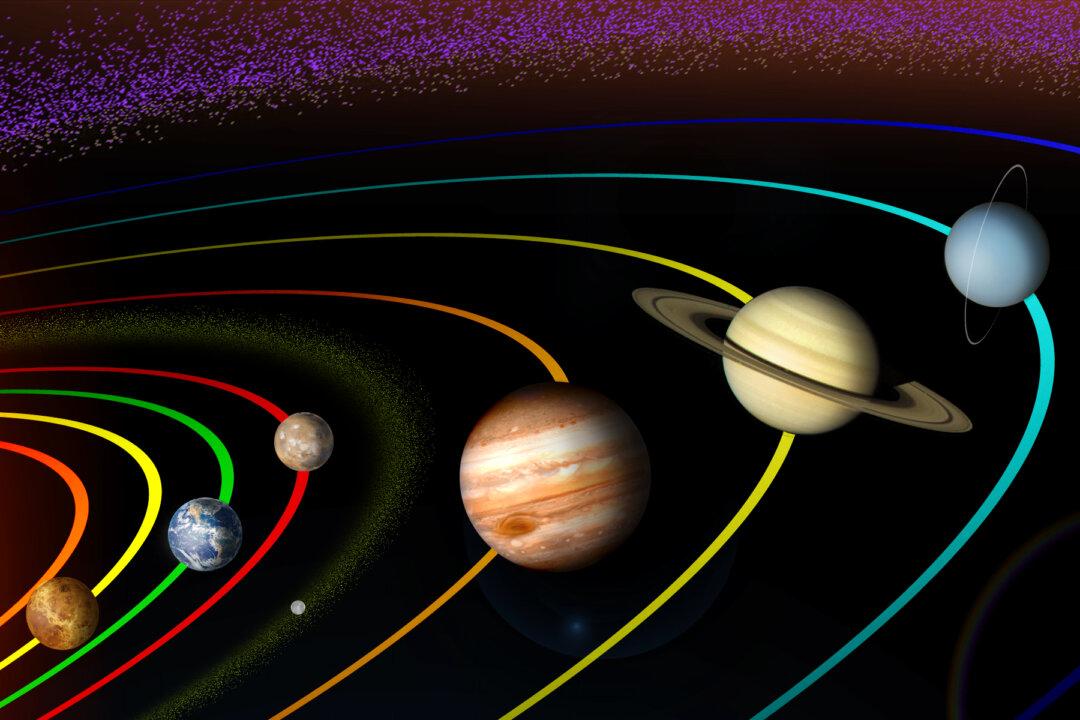

The Long Hunt for New Objects in Our Expanding Solar System

Astronomers are finding new exoplanets in other parts of the galaxy all the time. So why is it so hard to pin down exactly what is orbiting our own sun?

|

The Five Most Earth-Like Exoplanets (So Far)

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve read that the “first Earth-like exoplanet” has been discovered.

|

New Planet Hunting Telescopes See Success in First Year

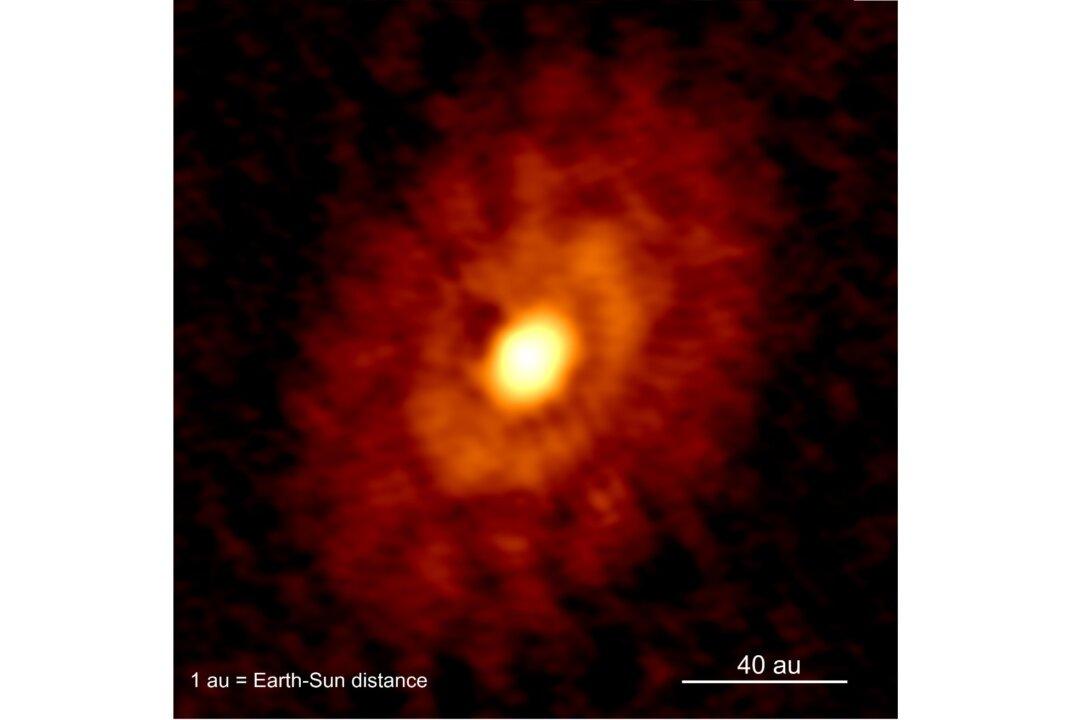

Stunning exoplanet images and spectra from the first year of science operations with the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) were featured today in a press conference at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Seattle, Washington. The Gemini Planet Imager GPI is an advanced instrument designed to observe the environments close to bright stars to detect and study Jupiter-like exoplanets (planets around other stars) and see protostellar material (disk, rings) that might be lurking next to the star.

|

Newly Discovered Exoplanets are Most Earth-Like Ones Ever Found (Video)

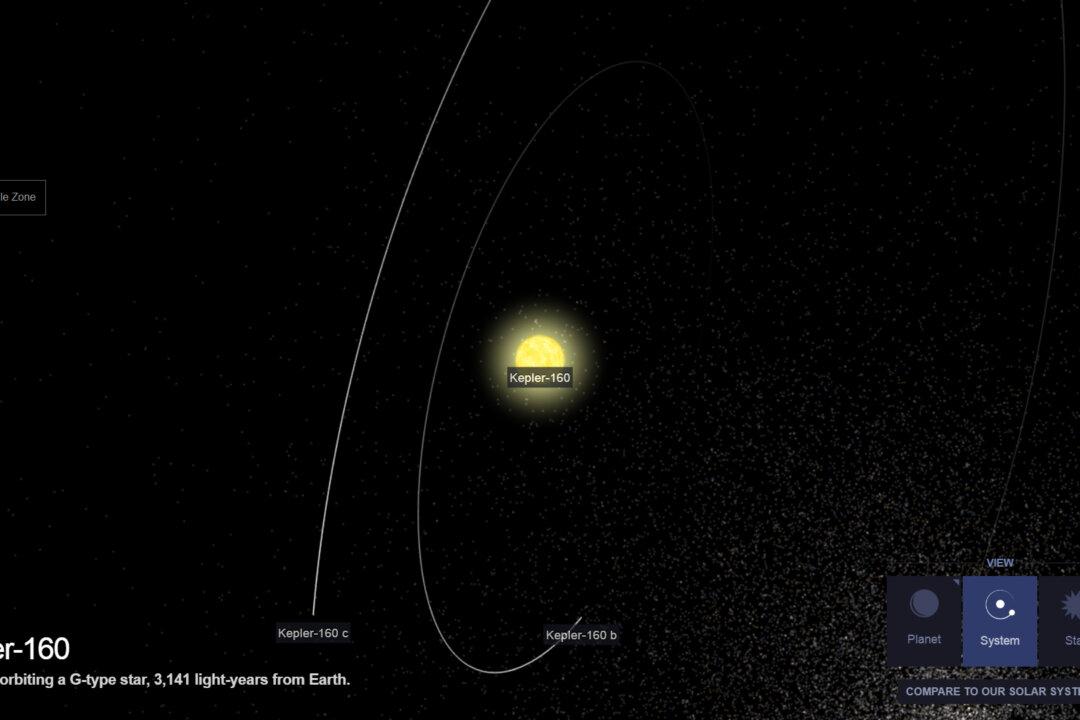

Two new exoplanets discovered via NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope are more like our own planet than any far-off celestial body ever examined.

|

|

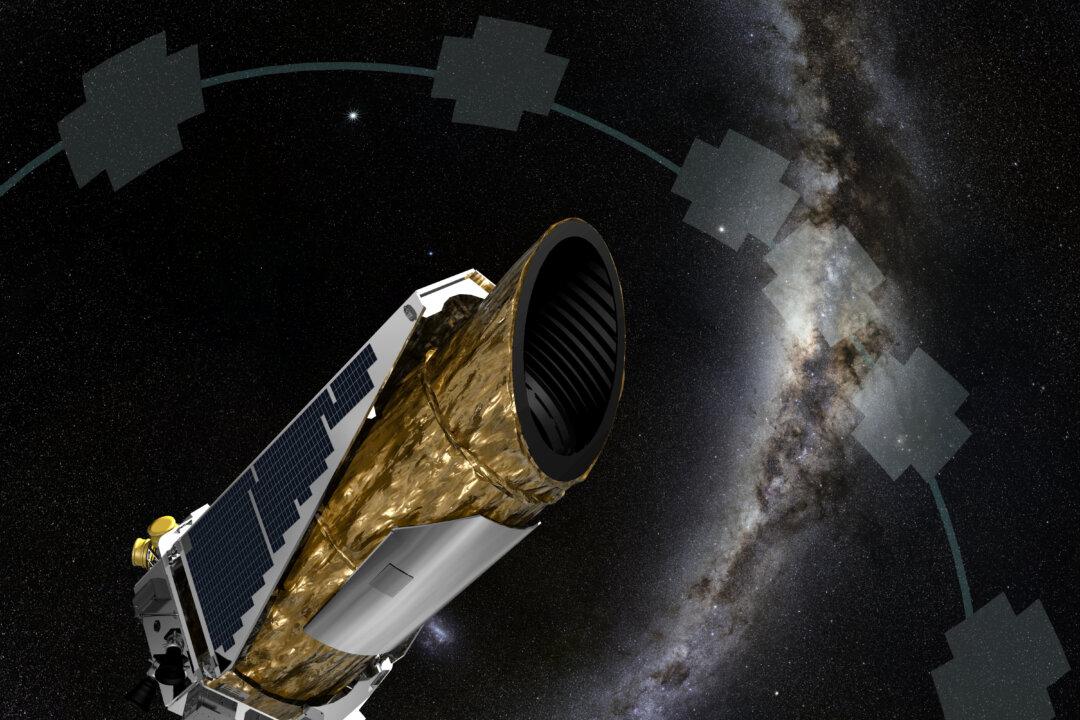

NASA’s Kepler Reborn, Makes First Exoplanet Find of New Mission

NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft makes a comeback with the discovery of the first exoplanet found using its new mission -- K2

|

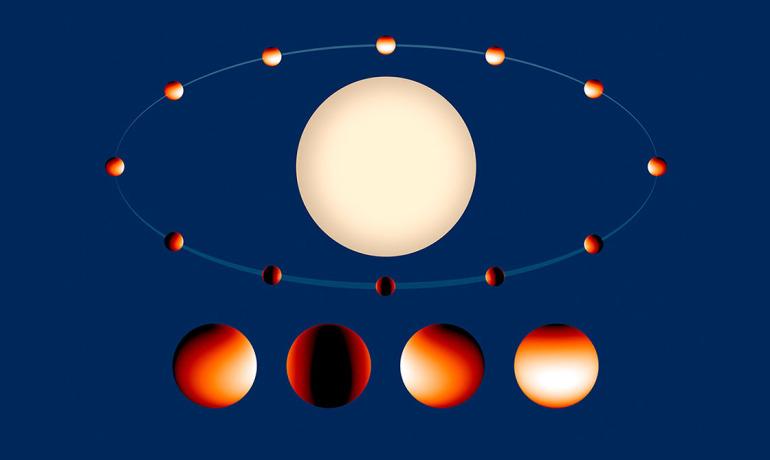

It’s Hot Enough on This Exoplanet to Melt Steel

The most detailed weather map ever made of an exoplanet orbiting another star 260 light-years away from Earth shows a world with daytime temperatures hot enough to melt steel.

|

To Find Alien Life, Search for Planets With Sidekicks

Exoplanets roughly the size of Earth may be more likely to support life if they have companion planets. Here’s why ...

|

Exoplanets Made of Diamonds: Do They Exist?

Scientists believe most exoplanets, which are located far beyond our solar system, are composed of elements similar to those found on Earth. But...

|

Search for Alien Life Could Remain Fruitless, Study Finds

Given that we are unlikely to be visiting an exoplanet any time soon, astronomers have been contemplating whether it might be possible to detect indications of simple life – a biosignature – from a distance.

|

A Different Spin – Exoplanet’s ‘Day’ Is Measured for the First Time

Over the past two decades, almost 1,500 exoplanets have been discovered orbiting distant stars – but Dutch astronomers have determined for the very first time just how fast one of those exoplanets is spinning on its axis.

|

Move Over Exoplanets, Exomoons May Harbour Life Too

In the Star Wars universe, everyone’s favourite furry aliens, the Ewoks, famously lived on the “forest moon of Endor”. In scientific terms, the Ewok’s home world would be referred to as an exomoon, which is simply a moon that orbits an exoplanet – any planet that orbits a star other than our sun.

|

Is Earth-Sized Exoplanet Just Right for Life?

Astronomers have for the first time discovered a rocky, Earth-sized exoplanet that might hold liquid water—a necessary ingredient for life as we know it.

|

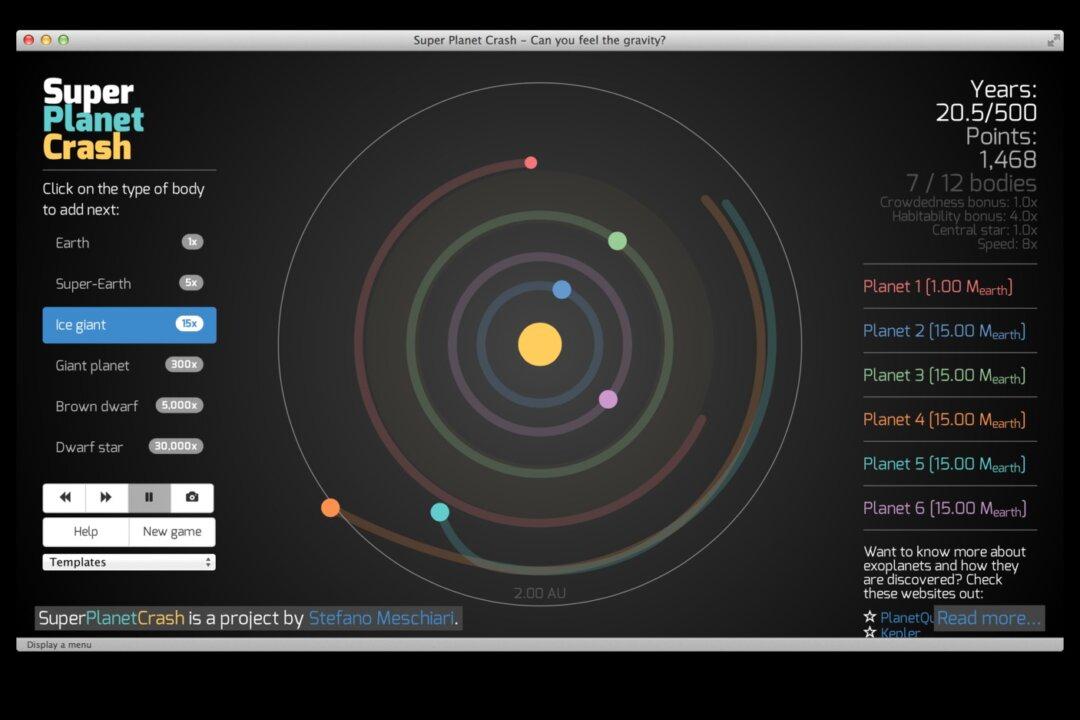

Telescope Apps Help Amateurs Hunt for Exoplanets

People around the world are being invited to learn how to hunt for planets, using two new online apps devised by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin and UC Santa Cruz.

|

NASA Announces 7 New Planets (Video)

Scientists confirmed the existence of seven new planets orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1.

|

The Long Hunt for New Objects in Our Expanding Solar System

Astronomers are finding new exoplanets in other parts of the galaxy all the time. So why is it so hard to pin down exactly what is orbiting our own sun?

|

The Five Most Earth-Like Exoplanets (So Far)

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve read that the “first Earth-like exoplanet” has been discovered.

|

New Planet Hunting Telescopes See Success in First Year

Stunning exoplanet images and spectra from the first year of science operations with the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) were featured today in a press conference at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Seattle, Washington. The Gemini Planet Imager GPI is an advanced instrument designed to observe the environments close to bright stars to detect and study Jupiter-like exoplanets (planets around other stars) and see protostellar material (disk, rings) that might be lurking next to the star.

|

Newly Discovered Exoplanets are Most Earth-Like Ones Ever Found (Video)

Two new exoplanets discovered via NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope are more like our own planet than any far-off celestial body ever examined.

|

|

NASA’s Kepler Reborn, Makes First Exoplanet Find of New Mission

NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft makes a comeback with the discovery of the first exoplanet found using its new mission -- K2

|

It’s Hot Enough on This Exoplanet to Melt Steel

The most detailed weather map ever made of an exoplanet orbiting another star 260 light-years away from Earth shows a world with daytime temperatures hot enough to melt steel.

|

To Find Alien Life, Search for Planets With Sidekicks

Exoplanets roughly the size of Earth may be more likely to support life if they have companion planets. Here’s why ...

|

Exoplanets Made of Diamonds: Do They Exist?

Scientists believe most exoplanets, which are located far beyond our solar system, are composed of elements similar to those found on Earth. But...

|

Search for Alien Life Could Remain Fruitless, Study Finds

Given that we are unlikely to be visiting an exoplanet any time soon, astronomers have been contemplating whether it might be possible to detect indications of simple life – a biosignature – from a distance.

|

A Different Spin – Exoplanet’s ‘Day’ Is Measured for the First Time

Over the past two decades, almost 1,500 exoplanets have been discovered orbiting distant stars – but Dutch astronomers have determined for the very first time just how fast one of those exoplanets is spinning on its axis.

|

Move Over Exoplanets, Exomoons May Harbour Life Too

In the Star Wars universe, everyone’s favourite furry aliens, the Ewoks, famously lived on the “forest moon of Endor”. In scientific terms, the Ewok’s home world would be referred to as an exomoon, which is simply a moon that orbits an exoplanet – any planet that orbits a star other than our sun.

|

Is Earth-Sized Exoplanet Just Right for Life?

Astronomers have for the first time discovered a rocky, Earth-sized exoplanet that might hold liquid water—a necessary ingredient for life as we know it.

|

Telescope Apps Help Amateurs Hunt for Exoplanets

People around the world are being invited to learn how to hunt for planets, using two new online apps devised by scientists at the University of Texas at Austin and UC Santa Cruz.

|