Focus

Canadian War Museum

LATEST

The Colosseum: Death and Glory in Ancient Rome

Exhibition at the Canadian War Museum showcases a day in the life of a gladiator.

|

World Press Photo Exhibit Opens at Canadian War Museum

The 2015 World Press Photo exhibit shows images of everyday life as well as what’s making headline news around the globe.

|

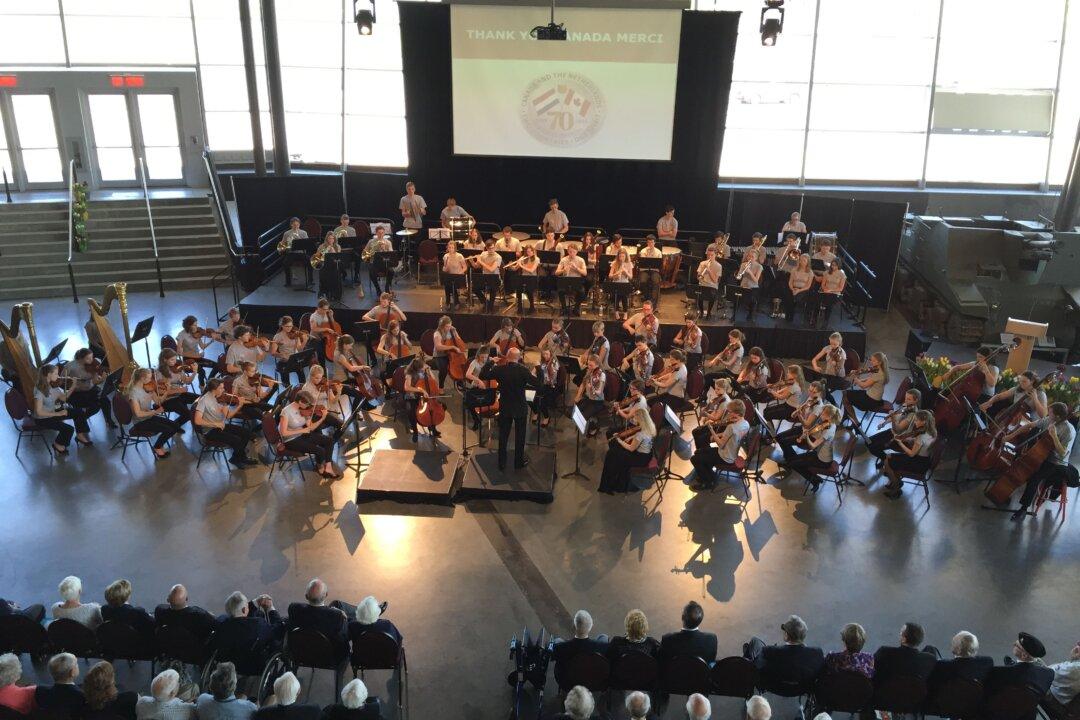

Dutch Youth Orchestra Plays for Canadian Vets

The Youth Orchestra of The Netherlands treat Canadian WWII vets to a very special private concert at the Canadian War Museum.

|

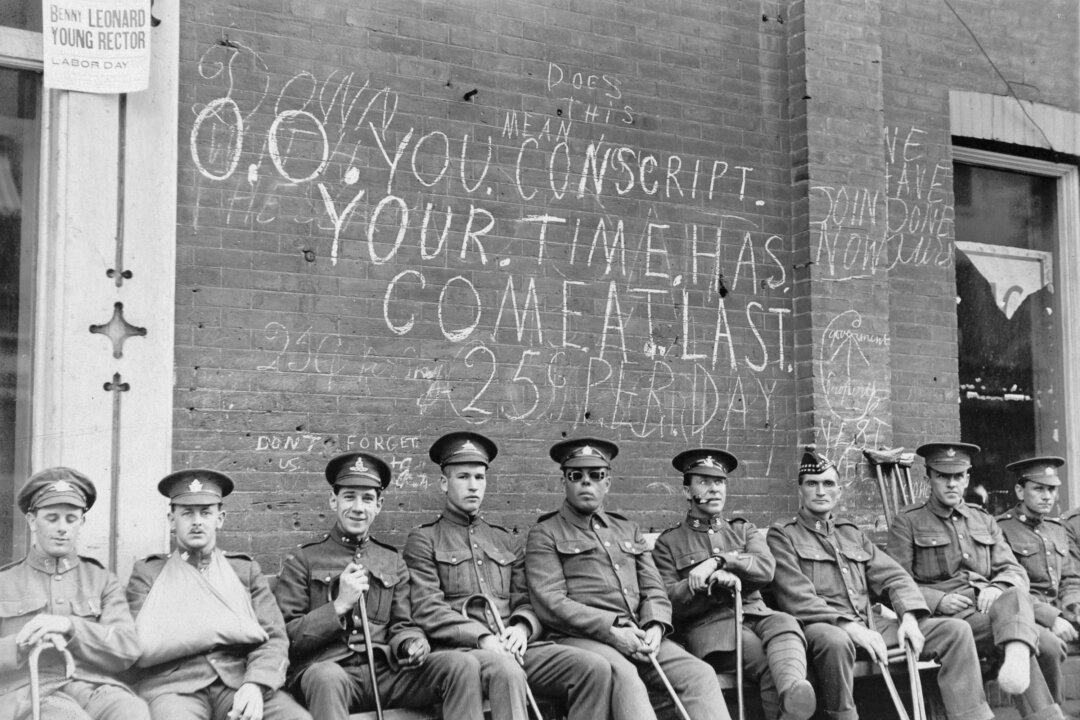

New Exhibit Examines Canada’s 1917 Conscription Crisis

In Canada in 1917, across the waters from war-torn Europe, discord and dissension took hold.

|

Gas, Mud, Memory: Exhibition Recalls WWI

“Fighting in Flanders: Gas, Mud, Memory” presents a pithy, incisive account of the carnage experienced in Flanders from 1914-18.

|

The ‘Persuasive Power’ of Photography in WW1

From the earliest days of photography, its use on the battlefield as a documentary tool was well-appreciated by the military. Matthew Brady’s photos of the American Civil War are but one well-known example of this. However, during the First World War, the medium of photography obtained important new tactical and strategic levels. Propaganda could be generated by the Allied command to look “really true.” Soldiers’ families, of course, wanted pictures of their loved ones.

|

Sculpture Exhibition Shows Wartime Humanity

‘Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times,’ 12 sculptures of war art, is on display at the Canadian War Museum.

|

Canada’s Bloody Coming of Age (+Video)

The First World War destroyed the romance of armed conflict and brought waves of death to Europe that forever changed the nature of battle.

|

|

Poignant Art in Canada’s Cold War Bunker

Not far from Parliament Hill in downtown Ottawa, a mere 35 km west as the crow flies, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s government of the day implemented a secret project centered on the design and construction of a bomb shelter.

|

The Legacy of Canada’s First Female War Artist

Ten small oil paintings by Molly Lamb Bobak have recently been installed in a memorial exhibition at the Canadian War Museum. Bobak (1920-2014) was the last of Canada’s WWII war artists.

Bobak joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps in 1942. In 1945 she was sent to the Netherlands, making her the first Canadian woman to be sent anywhere overseas as an official war artist. The Canadian War Museum has 115 of her artworks among its holdings.

|

Canadian War Museum Explores Peace

War and Peace are ever linked together. When bombs stop falling, when hostilities cease, people speak of a time of peace. Is the cessation of war the only requirement of peace? Too often, one war begets another, then another. What makes a “good peace?”

|

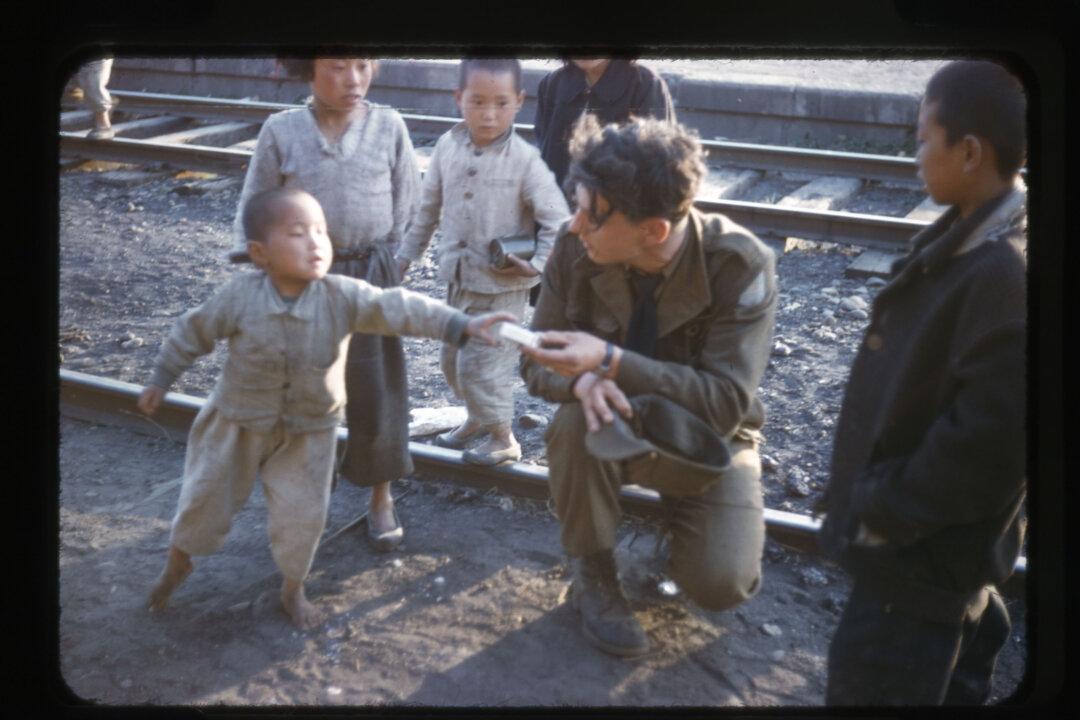

Korea 60 at the Canadian War Museum

On a long wall of the Canadian War Museum’s lobby area is a straightforward display of photographs, diagrams, and short didactic texts titled Korea 60. Visitors would be well advised to linger a little longer in front of this quiet display.

|

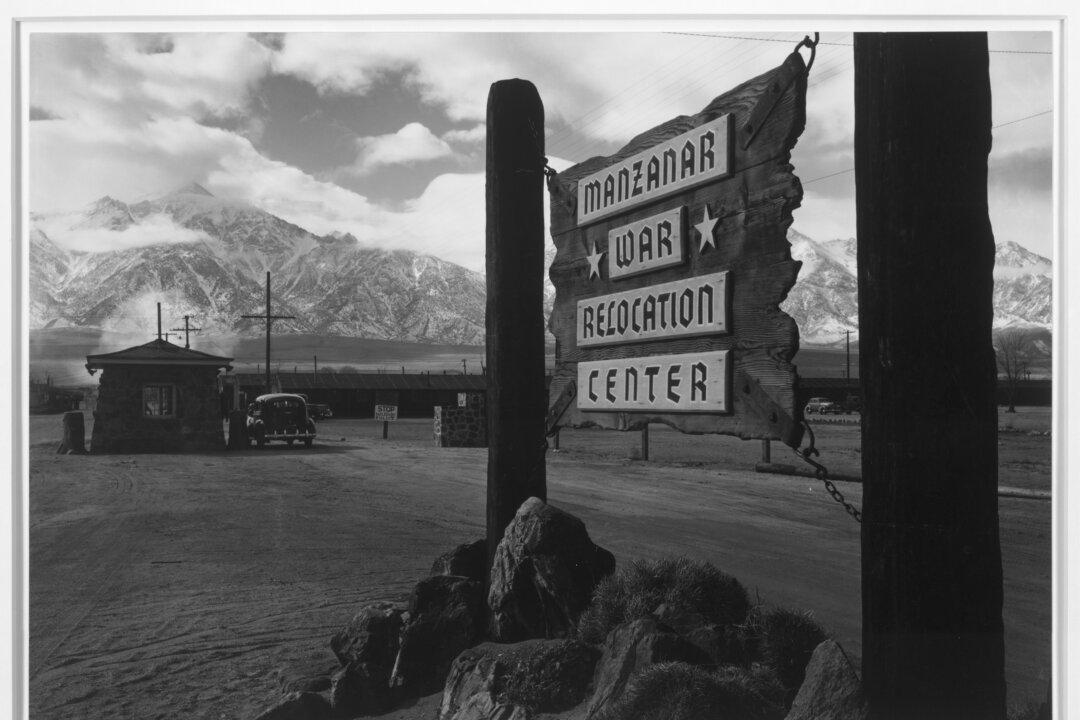

Two Views–Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank

American photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984) and Canadian photographer Leonard Frank (1870-1944) photographed the internment camps. Thirty-five black-and-white photographs have been selected for this exhibition.

|

War and its Impact on the Lives of 11 Women

OTTAWA—Photojournalist Nick Danziger’s documentary exhibition “Eleven Women Facing War” at the Canadian War Museum is intimate and intense.

|

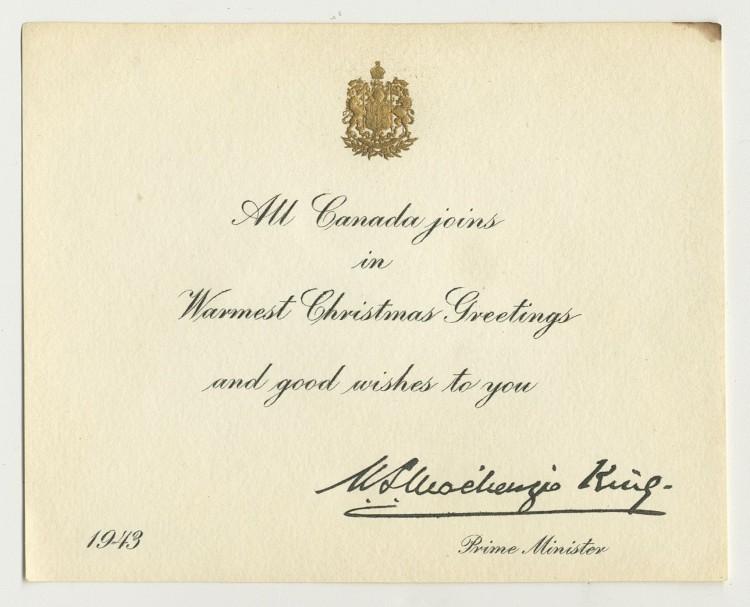

Historic Christmas Card Displayed at Canadian War Museum

Card from Prime Minister King to a Canadian PoW in 1943 is on display for the holiday season.

|

The Colosseum: Death and Glory in Ancient Rome

Exhibition at the Canadian War Museum showcases a day in the life of a gladiator.

|

World Press Photo Exhibit Opens at Canadian War Museum

The 2015 World Press Photo exhibit shows images of everyday life as well as what’s making headline news around the globe.

|

Dutch Youth Orchestra Plays for Canadian Vets

The Youth Orchestra of The Netherlands treat Canadian WWII vets to a very special private concert at the Canadian War Museum.

|

New Exhibit Examines Canada’s 1917 Conscription Crisis

In Canada in 1917, across the waters from war-torn Europe, discord and dissension took hold.

|

Gas, Mud, Memory: Exhibition Recalls WWI

“Fighting in Flanders: Gas, Mud, Memory” presents a pithy, incisive account of the carnage experienced in Flanders from 1914-18.

|

The ‘Persuasive Power’ of Photography in WW1

From the earliest days of photography, its use on the battlefield as a documentary tool was well-appreciated by the military. Matthew Brady’s photos of the American Civil War are but one well-known example of this. However, during the First World War, the medium of photography obtained important new tactical and strategic levels. Propaganda could be generated by the Allied command to look “really true.” Soldiers’ families, of course, wanted pictures of their loved ones.

|

Sculpture Exhibition Shows Wartime Humanity

‘Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times,’ 12 sculptures of war art, is on display at the Canadian War Museum.

|

Canada’s Bloody Coming of Age (+Video)

The First World War destroyed the romance of armed conflict and brought waves of death to Europe that forever changed the nature of battle.

|

|

Poignant Art in Canada’s Cold War Bunker

Not far from Parliament Hill in downtown Ottawa, a mere 35 km west as the crow flies, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s government of the day implemented a secret project centered on the design and construction of a bomb shelter.

|

The Legacy of Canada’s First Female War Artist

Ten small oil paintings by Molly Lamb Bobak have recently been installed in a memorial exhibition at the Canadian War Museum. Bobak (1920-2014) was the last of Canada’s WWII war artists.

Bobak joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps in 1942. In 1945 she was sent to the Netherlands, making her the first Canadian woman to be sent anywhere overseas as an official war artist. The Canadian War Museum has 115 of her artworks among its holdings.

|

Canadian War Museum Explores Peace

War and Peace are ever linked together. When bombs stop falling, when hostilities cease, people speak of a time of peace. Is the cessation of war the only requirement of peace? Too often, one war begets another, then another. What makes a “good peace?”

|

Korea 60 at the Canadian War Museum

On a long wall of the Canadian War Museum’s lobby area is a straightforward display of photographs, diagrams, and short didactic texts titled Korea 60. Visitors would be well advised to linger a little longer in front of this quiet display.

|

Two Views–Photographs by Ansel Adams and Leonard Frank

American photographer Ansel Adams (1902-1984) and Canadian photographer Leonard Frank (1870-1944) photographed the internment camps. Thirty-five black-and-white photographs have been selected for this exhibition.

|

War and its Impact on the Lives of 11 Women

OTTAWA—Photojournalist Nick Danziger’s documentary exhibition “Eleven Women Facing War” at the Canadian War Museum is intimate and intense.

|

Historic Christmas Card Displayed at Canadian War Museum

Card from Prime Minister King to a Canadian PoW in 1943 is on display for the holiday season.

|