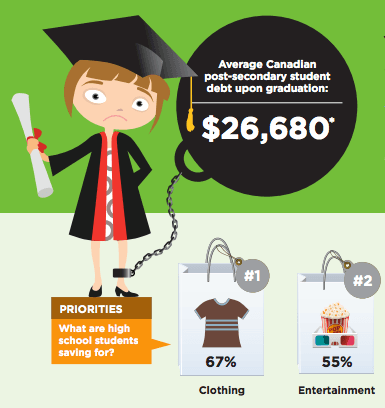

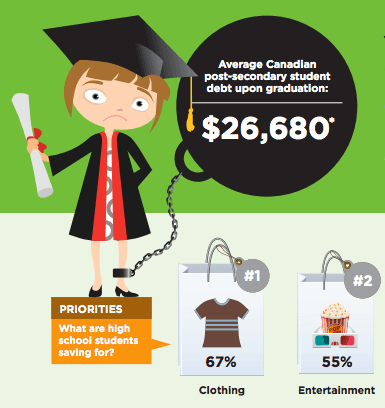

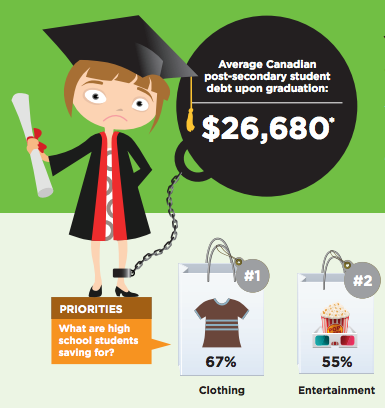

As Canadians sink deeper into debt amidst a growing consumer culture, the idea that Canadians need an education in financial literary is gaining traction. This is exactly what the Investor Education Fund (IEF), a non-profit established by the Ontario Securities Commission, has been doing for the last decade.

“It’s a tough subject. People don’t like to speak about it and they’re not necessarily all that interested in it, so you really have to engage them on a level that they’re comfortable [with],” explained IEF vice-president Perry Quinton.

Quinton was at this year’s kickoff of Financial Literacy Month, a new annual event each November aimed at helping Canadians strengthen their knowledge, skills, and confidence to make responsible financial decisions.