Commentary

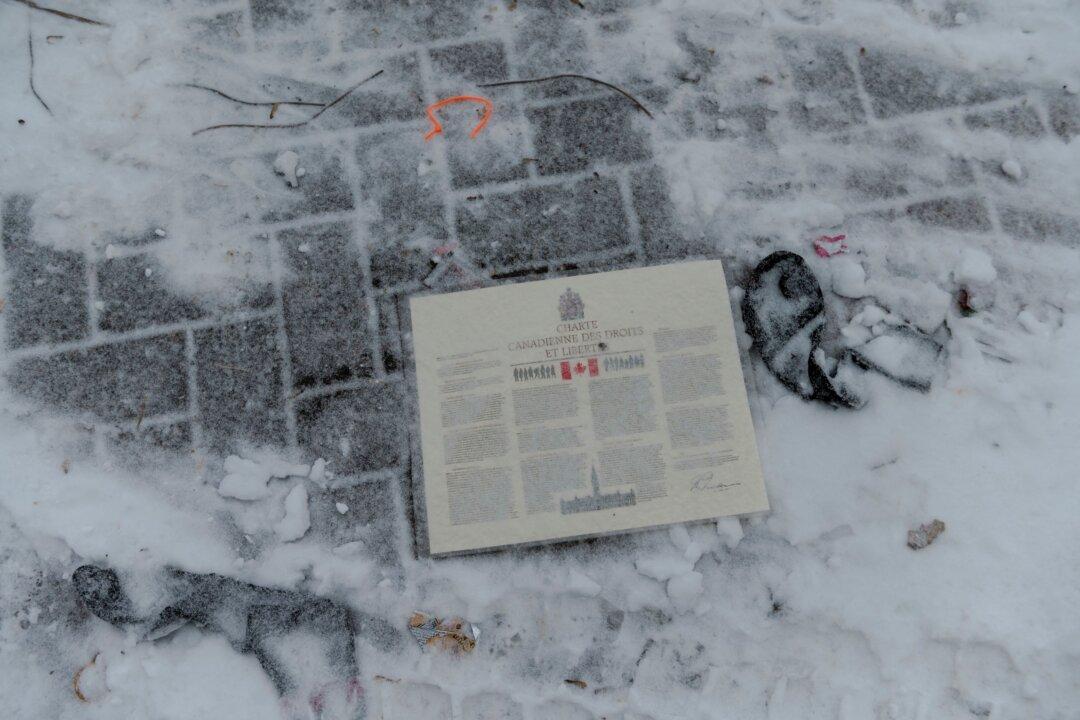

Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognized “the Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada,” explicitly including “Métis peoples.” At the time, however, the Constitution’s framers offered no clear idea of what they meant by “Métis.