Fifteen years after the Twin Towers were brought down by terrorist attacks on 9/11, the war in Afghanistan rages on.

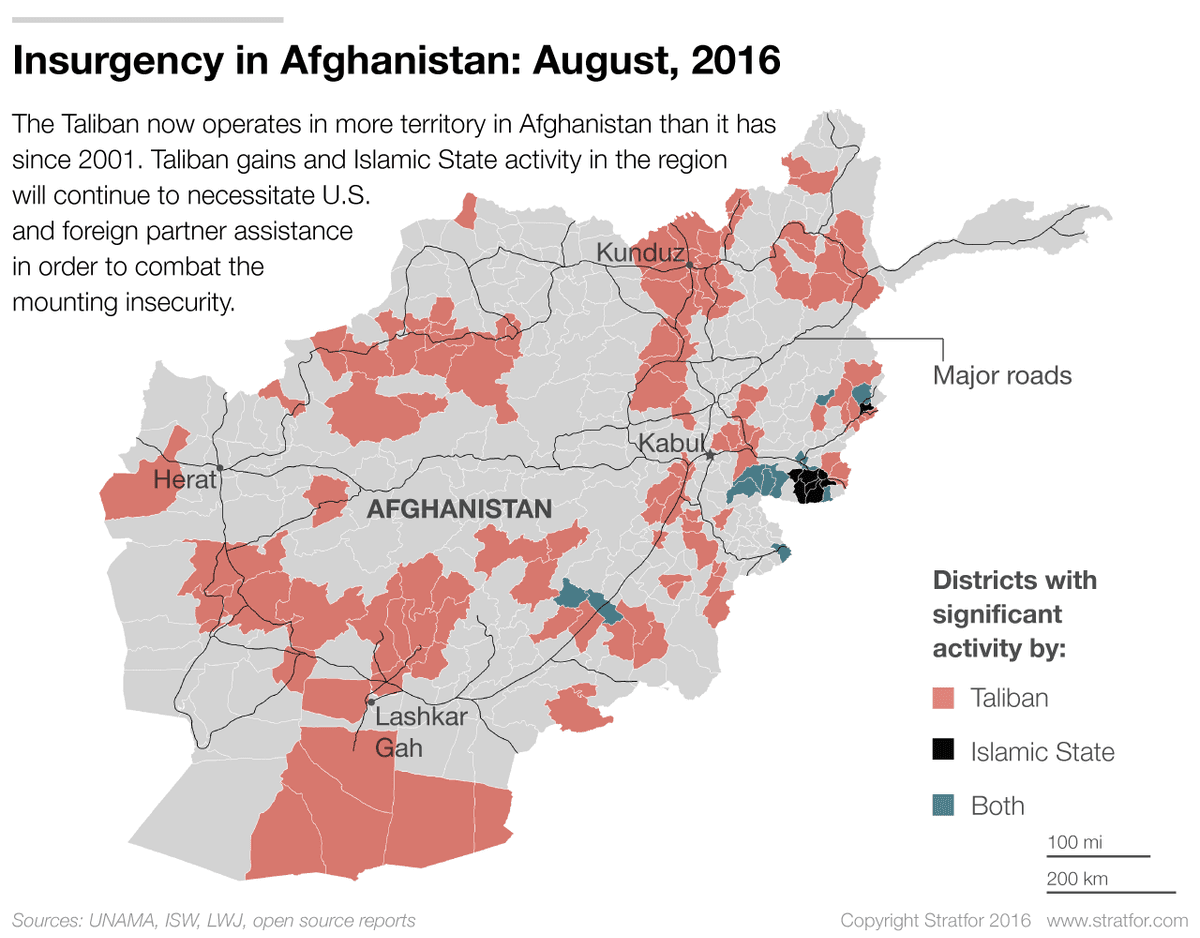

Taliban and other insurgent groups have gained momentum against U.S.-backed Afghan security forces and pose a serious threat in 116 out of the country’s 384 districts, said Timor Sharan, senior Afghanistan analyst for International Crisis Group, citing official Afghan sources.

“This gives a clear indication of the growing insurgency that is seriously challenging the Afghan government in many different parts of the country,” he said.

The core challenge is political, rather than martial, say experts. The National Unity Government (NUG) of Afghanistan has been plagued by internal squabbling, making it less effective against the insurgency.

As a result, the security forces have lower morale, and much of the country is contested.