Commentary

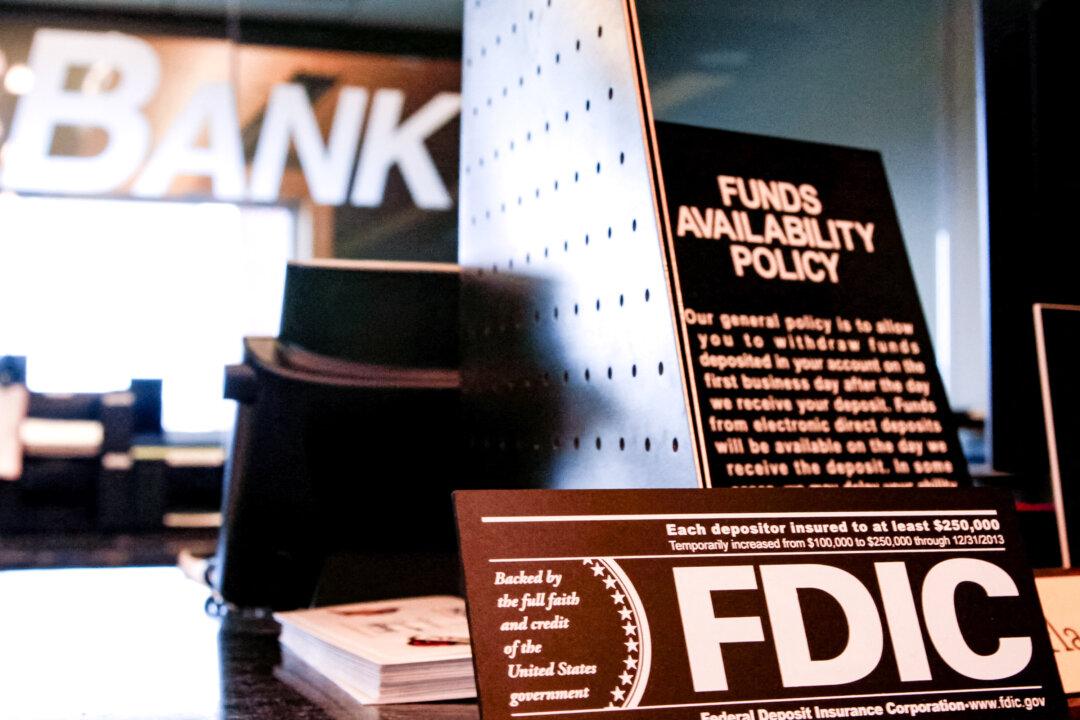

Rate hikes tend to shock the financial markets, both faster and more decisively, than they affect the wider economy. That effect on markets, in turn, can slow the consumer economy—usually the biggest part of GDP—because it negatively affects the wealth effect, the propensity of people to spend more because their assets are worth more. Rate increases also tend to move across credit markets, affecting everything from commercial paper to adjustable rate mortgages when they re-set. The effects are nearly instantaneous and can sometimes have an acute and disruptive effect on the economy.