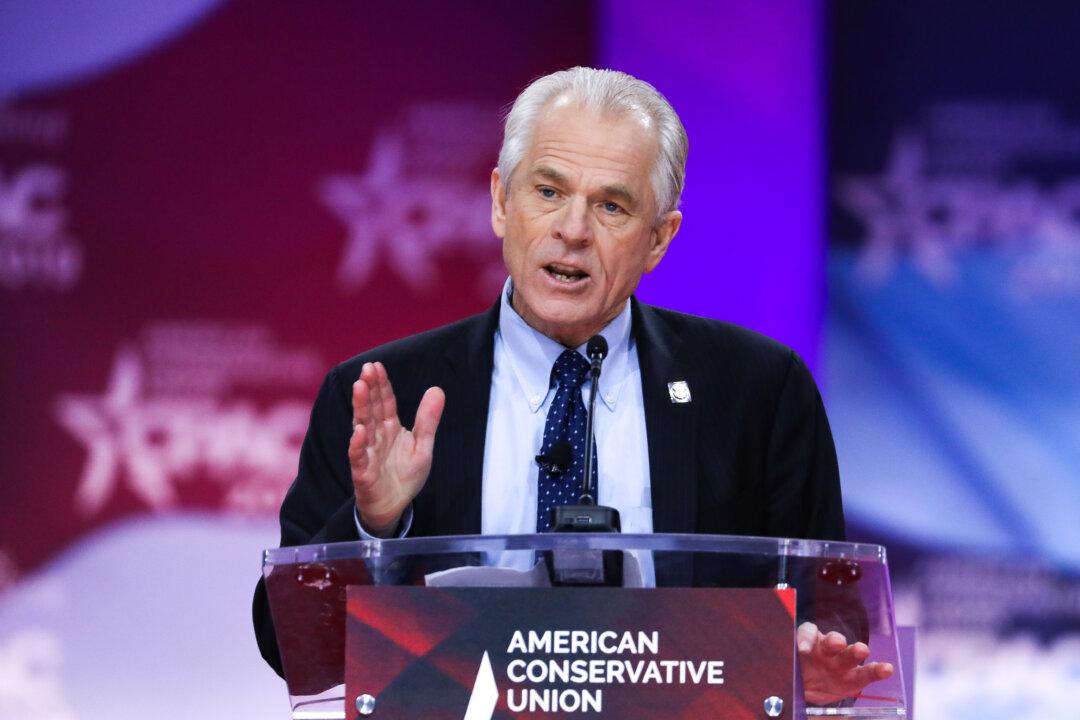

Roger Garside, a noted China expert and British former diplomat who was stationed in Beijing during and after the reign of Mao Zedong, discussed his vision on Monday for democracy in China in an event hosted by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Garside, author of “China Coup: The Great Leap to Freedom,” which was published this month by University of California Press, stated that outsiders “cannot dictate how China is governed. But they can and must help those Chinese who want a democratic China to achieve it.”