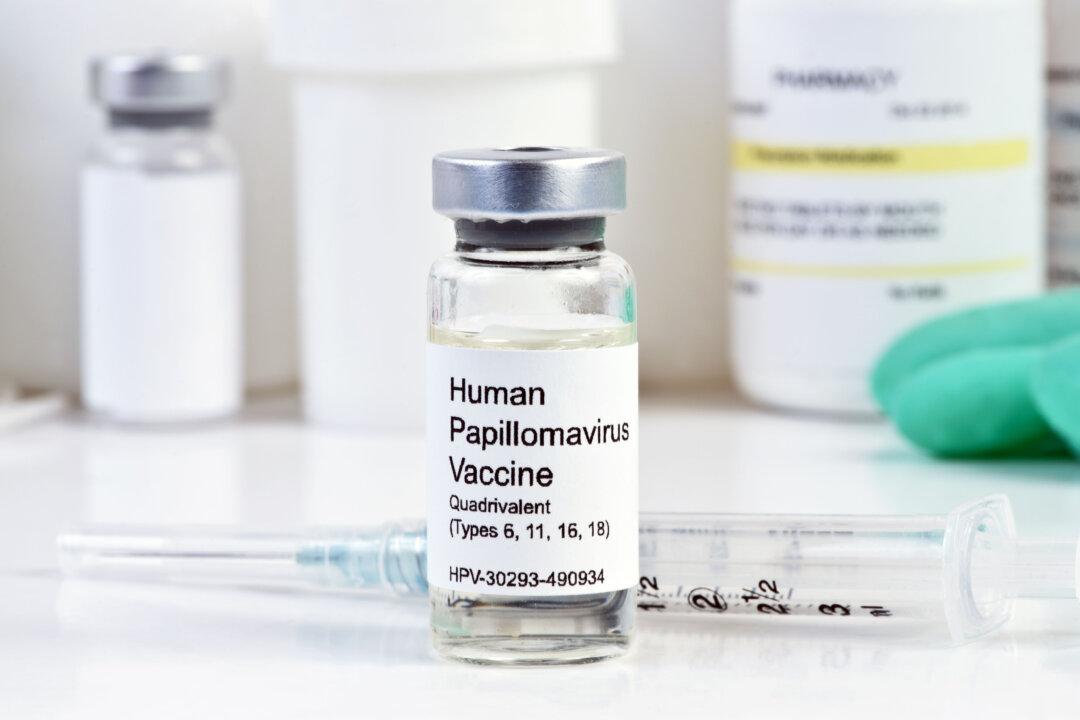

The decline of public trust in COVID-19 vaccines significantly impacts vaccination rates against routine childhood diseases. This multiple-part series explores the international research done over the past two decades on the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine—believed to be one of the most effective vaccines developed to date.

Summary of Key Facts

- This multiple-part series offers a thorough analysis of concerns raised about HPV vaccination following the global HPV campaign, which commenced in 2006.

- In the United States, the HPV vaccine was reported to have a disproportionately higher percentage of adverse events of fainting and blood clots in the veins. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledges that fainting can happen following the HPV vaccine, and recommends sitting or lying down to get the shot, then waiting for 15 minutes afterward.

- International scientists found that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) logged a substantial increase in reports of premature ovarian failure (POF) from 1.4 per year before 2006 to 22.2 per year after the HPV vaccine approval, yielding a Proportional Reporting Ratio of 46.1.

In this HPV vaccine series, Parts I and II explain how the vaccine works and the evidence suggesting there may be legitimate safety concerns. The remaining parts present questions about real-world vaccine effectiveness and identify specific ingredients which may pose harm.