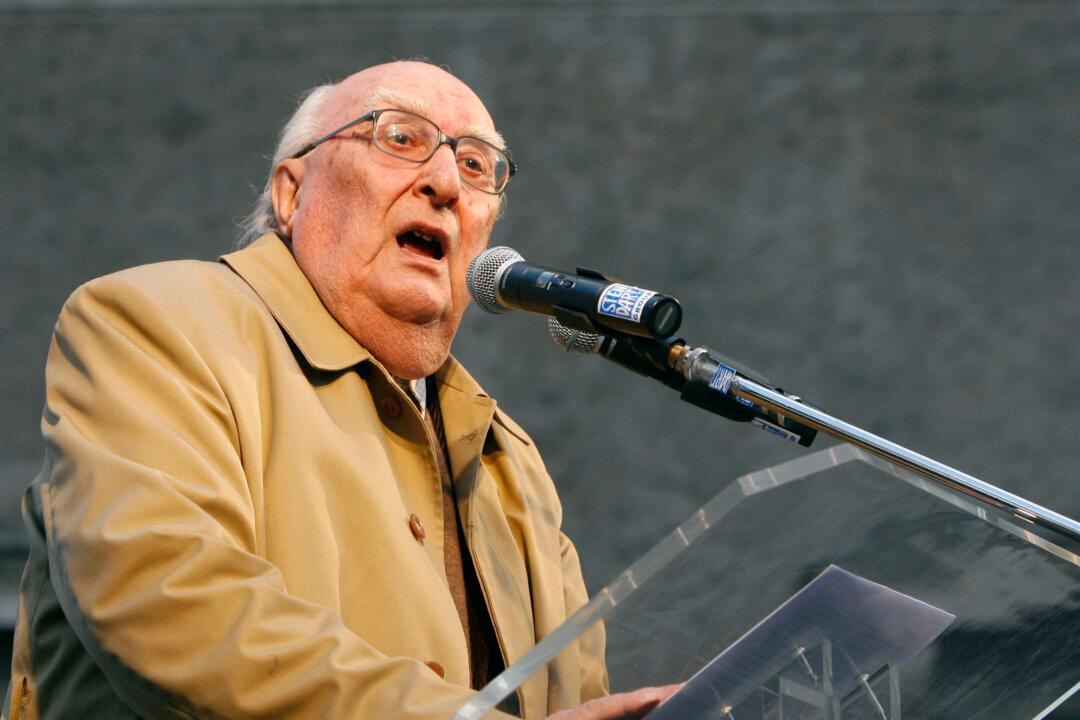

ROME—Author Andrea Camilleri, creator of the best-selling Commissario Montalbano series about a likable, though oft-brooding small-town Sicilian police chief who mixed humanity with pragmatism to solve crimes, died in a Rome hospital Wednesday. He was 93.

Italy’s RAI state TV, which produced wildly popular TV versions of his detective stories, interrupted its programming to announce his death and comment on his works.