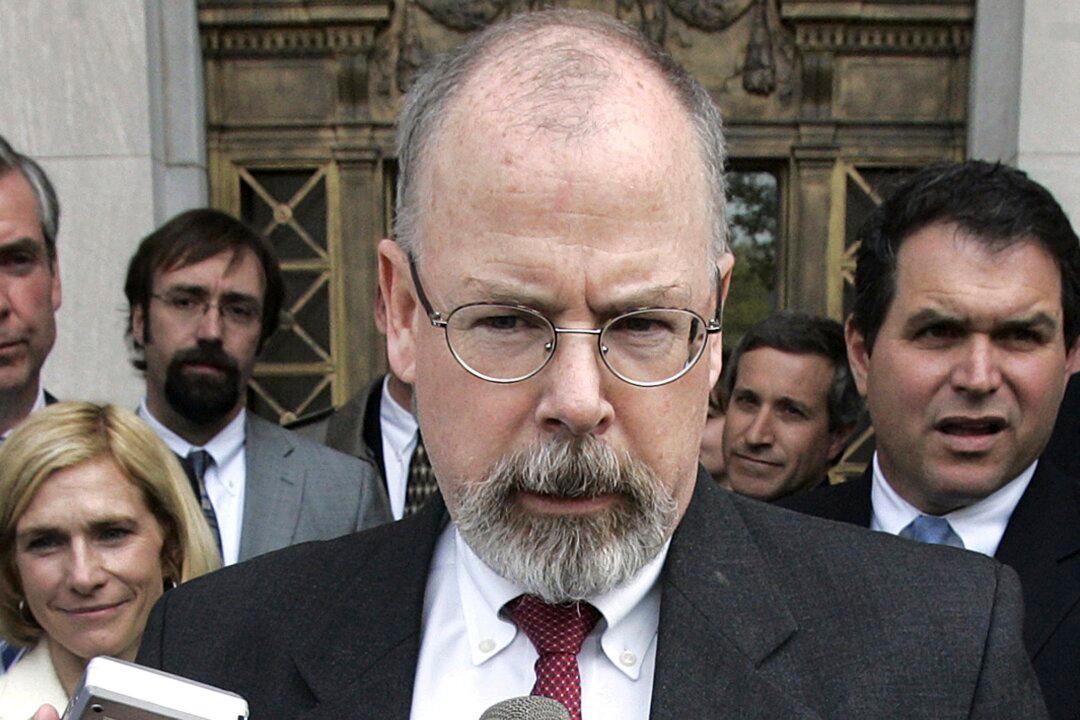

Special counsel John Durham may have sufficient grounds to seek charges against multiple parties for conspiracy to lie to the government, although he may refrain from doing so, according to a former FBI special agent and federal prosecutor.

Durham is already saying there was a “joint venture” between various parties, including agents of the 2016 presidential campaign of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the lawyers retained by the campaign, and their associates and subcontractors. The goal of the venture was to collect dirt in 2016 on then-presidential candidate Donald Trump in order to help Clinton. That isn’t illegal.