Commentary

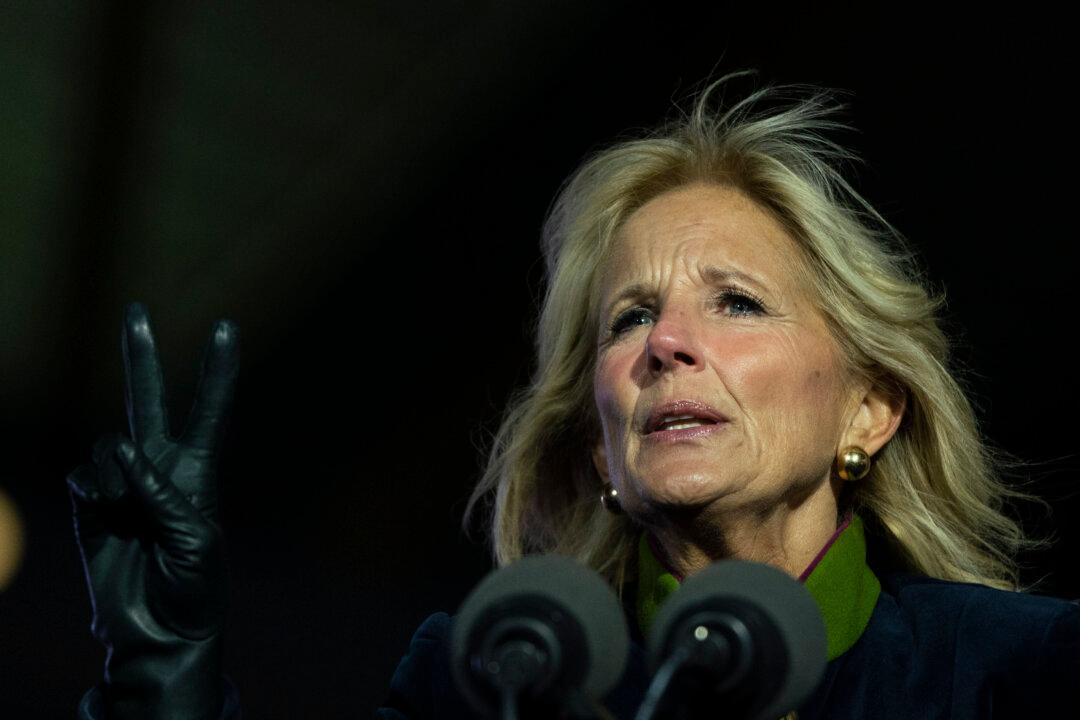

By now you’ve probably heard about the controversial article in the Wall Street Journal about Jill Biden by Joseph Epstein who says her use of the title doctor “sounds and feels fraudulent, not to say a touch comic.” The article was snarky and disrespectful but nonetheless leads to some interesting issues that need to be discussed.