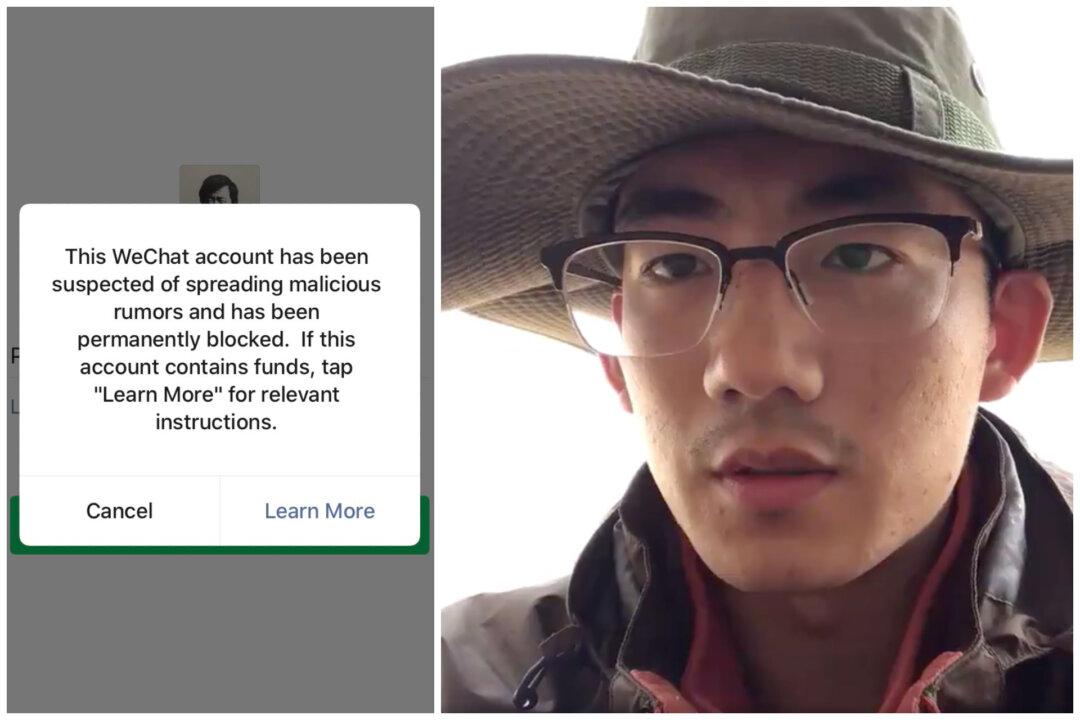

A college student in China has gone incommunicado after he publicly called for the country’s ruling Communist Party to relinquish power.

“Down with the Communist Party,” Zhang Wenbin, a college senior and programmer from China’s northeastern Shandong Province, said in a March 30 video on Twitter, a platform blocked in China. The student used a VPN, a tool used by Chinese citizens to access overseas websites censored by the regime’s internet firewall.