Caring for someone with a serious illness stretches people spiritually and emotionally, often beyond what they might have thought possible.

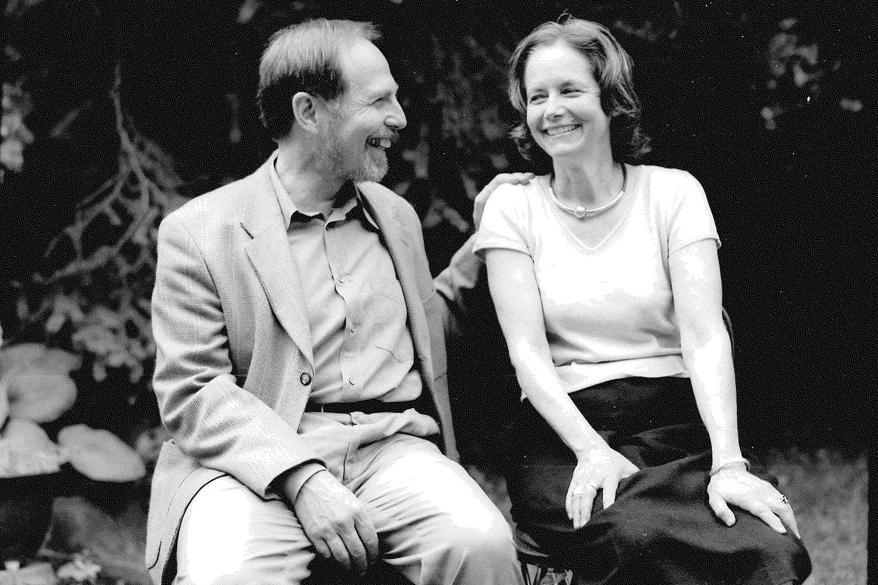

Dr. Arthur Kleinman, a professor of psychiatry and anthropology at Harvard University, calls this “enduring the unendurable” in his recently published book, “The Soul of Care: The Moral Education of a Husband and a Doctor.”