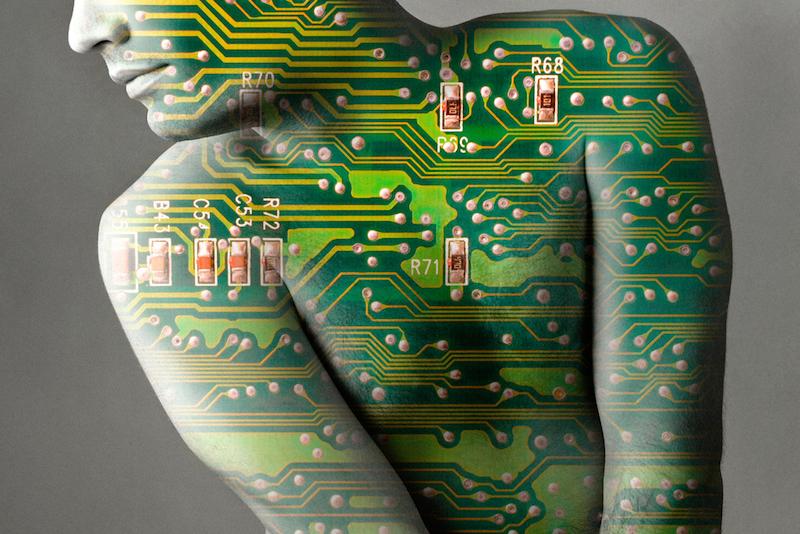

Moments after Neo eats the red pill in “The Matrix,” he touches a liquefied mirror that takes over his skin, penetrating the innards of his body with computer code. When I first learned about the controversial new digital drug Abilify MyCite, I thought of this famous scene and wondered what kinds of people were being remade through this new biotechnology.

Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and Proteus Digital Health won Food and Drug Administration approval to sell Abilify MyCite in late 2017. This drug contains a digital sensor embedded within the powerful antipsychotic drug Abilify, the brand name for aripiprazole, which is used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. The goal of the digital sensor is for doctors to monitor their patients’ intake of Abilify MyCite remotely and ensure that the patient is adhering to the correct drug dose and timing.