Commentary

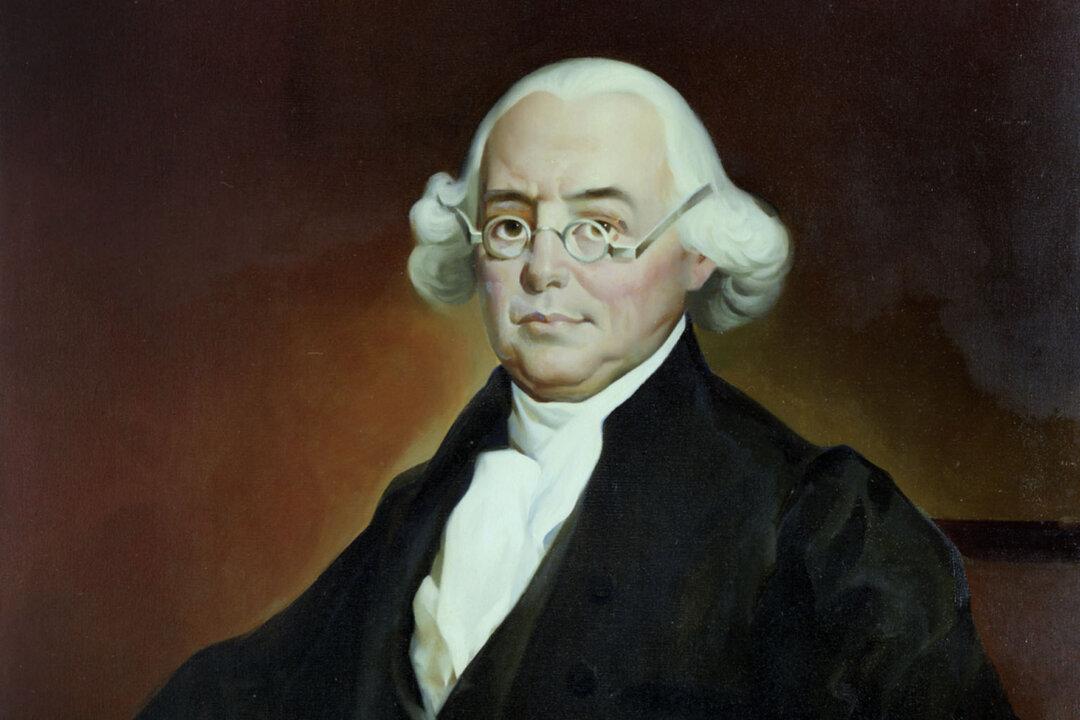

James Wilson of Pennsylvania (1742–98), a distinguished lawyer who eventually served on the U.S. Supreme Court, was one of the most influential of the Constitution’s framers. Some scholars rank him as second only to James Madison.

James Wilson of Pennsylvania (1742–98), a distinguished lawyer who eventually served on the U.S. Supreme Court, was one of the most influential of the Constitution’s framers. Some scholars rank him as second only to James Madison.