When you ask San Franciscans what’s great about the sort of people, the characteristics, or the culture of their neighborhood, the answer almost always includes “it’s a mix.”

The city prides itself in being able to preserve a certain culture that seems to take from all cultures, and its planning code ensures that what makes the city unique isn’t overturned on a whim just because the economy favors development.

Every project goes through a planning process that more often than not requires multiple back-and-forths. Anything constructed over 50 years ago is up for historic preservation consideration, and community input is the cornerstone of that process.

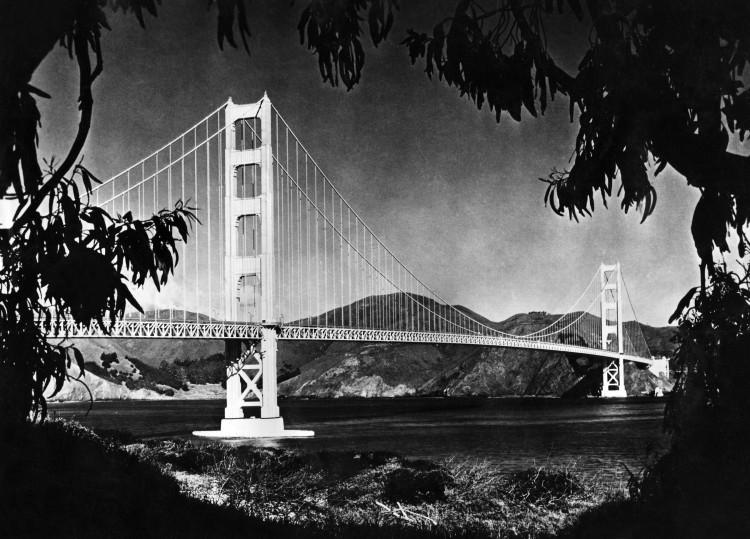

“San Francisco is a very beautiful city, and a lot of people see it as a very precious place to preserve,” says Michel St. Pierre, director of planning and urban design for EHDD in San Francisco.

“Too many opinions make projects hard to get through. It gets a lot of input, and very good solutions, … but it creates a longer time frame to get projects approved,” says St. Pierre. He has also worked on projects in China, which, in stark contrast to San Francisco’s almost crowd-sourced planning, has a very top-down process.

Compared to New York City, San Francisco only has one-seventh of the land area and a tenth of its population, but it reviews four times as many building projects. This city just has a different process.

“Every neighborhood is very distinct,” St. Pierre said. “Some work very hard to preserve their unique identity.”

“It’s too tall,” or “It all looks the same,” are common worries heard throughout community meetings in areas where development projects are picking up steam.

While this doesn’t allow for much boundary-pushing in terms of design, SoMa provides for a great experimental playground.

“South of Market is where we can do it,” St. Pierre said. “It’s very hard to create more density in these areas like North Beach and Chinatown, but South of Market there’s a lot of access to open space, and so on.”

A good portion of the buzz and activity in SoMa centers on the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA).

Mario Botta’s SFMOMA expansion in the 1990s set a sort of precedent in the development of the South-of-Market area, says Craig Dykers, New York CEO and co-founder of the architectural firm Snohetta, which is working on a further expansion of the museum.

“It was somewhat derelict and surrounded by parking lots,” Dykers said. The SFMOMA became a hub downtown, and major streets like Howard and 3rd Street were developed at around the same time.

“Our design is slightly different,” Dykers said. The museum currently sits in the core of the block, and “in the middle of the blocks are smaller alleyways, which have been forgotten about for a number of years.”

To integrate the museum into the city as much as possible, the design incorporates these alleyways in hopes of creating paths like Maiden Lane in Union Square, to be a “vibrant part of the city’s identity.”

San Francisco’s biggest charm, for Dykers, is the mix in its natural environment. Microclimates vary from neighborhood to neighborhood: “There are multiple grids coming together, and the most fantastic thing is the topography, which is unique in the world.”

“We think our building is helping to open up the intimate space,” Dykers said.

Atmosphere

Open space requirements in the downtown area are part of the planning code, and are among citizens’ biggest concerns when it comes to design.

“Buildings should be very engaged, both from the social and physical perspective,” St. Pierre said. The Exploratorium EHDD worked on aims to be the biggest net-zero energy consumption museum in the nation, if not the world. “We try to have a minimal impact in terms of shade and wind in the city—the building has to be very responsible.”

Responsible but beautiful, St. Pierre says.

Responsible design has long been a goal, and now in a city that’s become harder and harder to live in, it’s practically a requirement. Most major projects being developed include more open space than required, which the communities like—even if the buildings are too big or blocky for their tastes. The complaints that remain, then, are largely about style, complaints about the shape or façade—which aren’t as unfounded as they might sound.

“All buildings should have generosity associated with their design,” Dykers said. Snohetta, which was listed as one of the 50 most innovative companies by Fast Company for “social and beautiful” design, holds “engagement of the public” at the core of its philosophy.

“The attachment to public domain is very important,” Dykers said. “We design to people who move along streets, the eye-level of pedestrians, to the human scale. We want to provide an experience that’s valuable.”

It’s even more important in urban areas. “As we exist in cities, we find ourselves in closer context with other humans,” Dykers said. Design, the way the city looks, “has to promote civilized behavior as much as other politics or other thinking should.”

But South of Market isn’t just seeing renovation and redesign to underutilized spaces; it’s getting an entirely new neighborhood in the form of a rapidly materializing Mission Bay.

New Community?

In the last five to six years, St. Pierre said, the city has been seeing more of these big, glassy buildings being built.

“It’s a very unique city. It can create a very interesting blend,” St. Pierre said.

“There’ve been very groundbreaking modern buildings in the last five, six years, and it’s really changed the pattern, in a way, which is a good thing,” said St. Pierre.

They’re buildings that would stick out like a sore thumb in those more established 40-foot-height-zone neighborhoods, but perhaps they'll become a staple of the new neighborhood.

“There’s the ability to do interesting modern architecture today that is actually quite exciting,” St. Pierre said. “There’s an openness today that is very refreshing.”

A large amount of the building comes from the boosted housing market, and a larger amount is due to the Bay Area’s thriving tech sector.

“It’s interesting today because the economy is very positive in the city,” St. Pierre said.

St. Pierre says in his stay he’s seen San Francisco influenced by Silicon Valley in two waves—the first in the dot-com boom that resulted in the start-up mentality that populates the city, and the second “much more in urban districts.”

“The market has been completely transformed by the tech sector, and the city has really embraced it,” St. Pierre said.

While the city has certainly embraced the innovation and start-up mentality, many place the blame for the rise in real estate prices on tech workers who want to live in San Francisco but work in the Valley.

“San Francisco is becoming more exclusive, but the region is becoming more vibrant,” St. Pierre said. “However, what’s happening is that the cities nearby are benefiting greatly from a resurgence of a lot of young people moving into cities like Oakland.”

“It’s the reality of the marketplace that we just have to accept,” St. Pierre said. But if the city is really “designed by democracy,” as he says, and residents want to stay, the city could find a way to make it happen. Affordable housing is among the mayor’s top priorities, and Proposition C, which passed last November, contributes $1.3 billion over the next 30 years to housing.

Even in neighborhoods with a 40-foot mix of Victorian houses, Parisian buildings, and structures a century old, it should be taken into consideration that they are mixed because new styles were allowed to be incorporated, Dykers said.

“Sometimes when we want to ensure that the diversity of our surroundings is protected, people overreact with fear to globalization in our society,” Dykers said. “Not everything can be unique to location.”

“I think what makes the world interesting is that we share cultural traits,” Dykers said. “We have to think a lot about it and … protect those things that are unique while also allowing ideas coming [from] other places.”