Senate Democrats are trying to push Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) into voting to weaken the filibuster so that Democrats can pass voting rights legislation, after the senator from West Virginia on Jan. 4 rejected a strategy that would allow his party to work around Republican opposition to the measure.

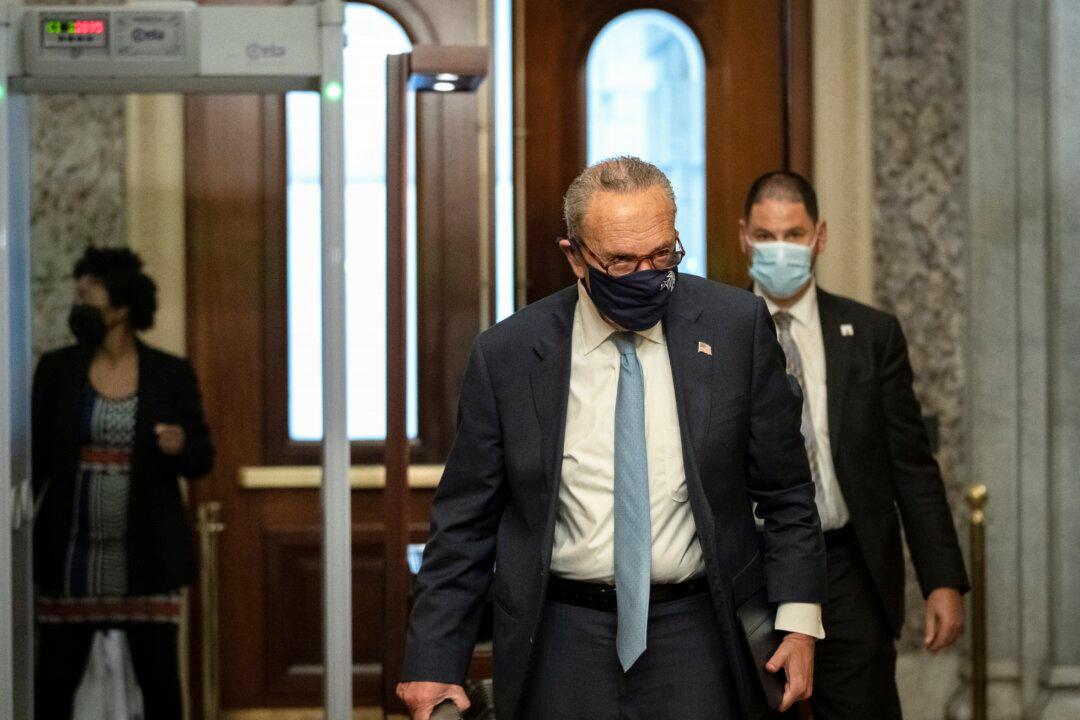

In a statement on his Twitter account on Jan. 3, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) attempted to tie GOP opposition to federal election bills to “domestic extremists” who, Schumer contended, tried to “destroy our Republic” in the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol breach.