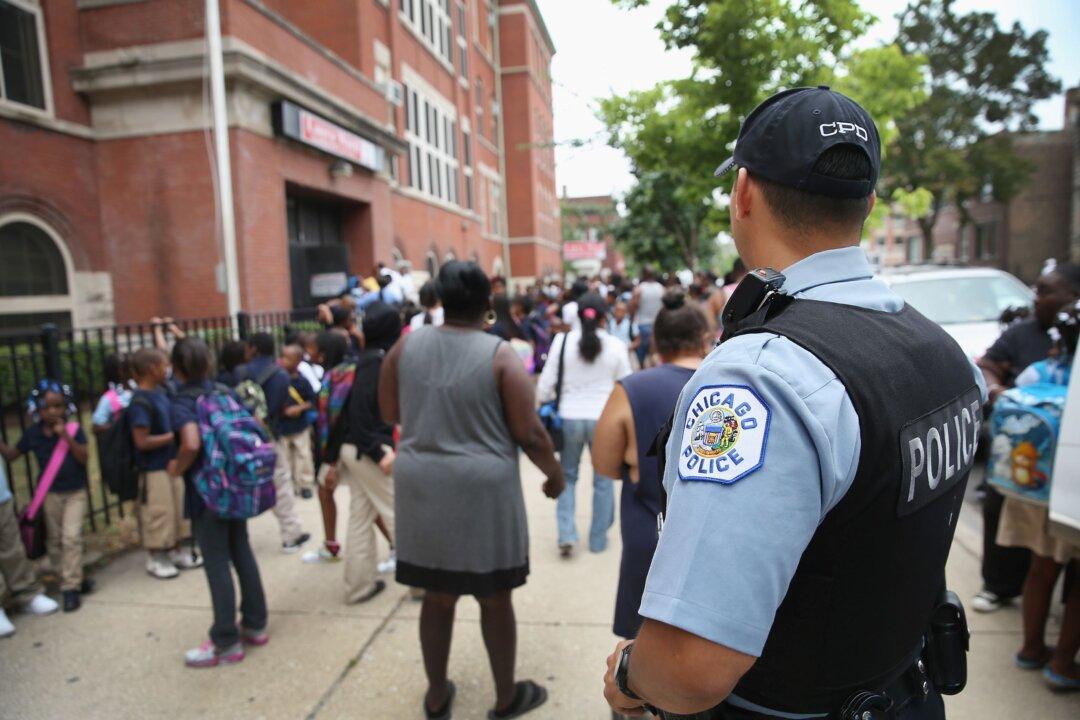

CHICAGO—For the new school year beginning in the fall, more Chicago public high schools are opting to remove on-campus police officers, a movement that gained momentum citywide last summer after the death of George Floyd.

Among about 45 high schools that retain officers, eight out of 10 are in the most violent neighborhoods on the South Side and West Side of the city, and most of their student bodies are predominantly African American.