This past Hall of Fame weekend that sadly saw the induction of three deceased baseball treasures was a true commentary on how steroids and other assorted fixations have poisoned the national pastime.

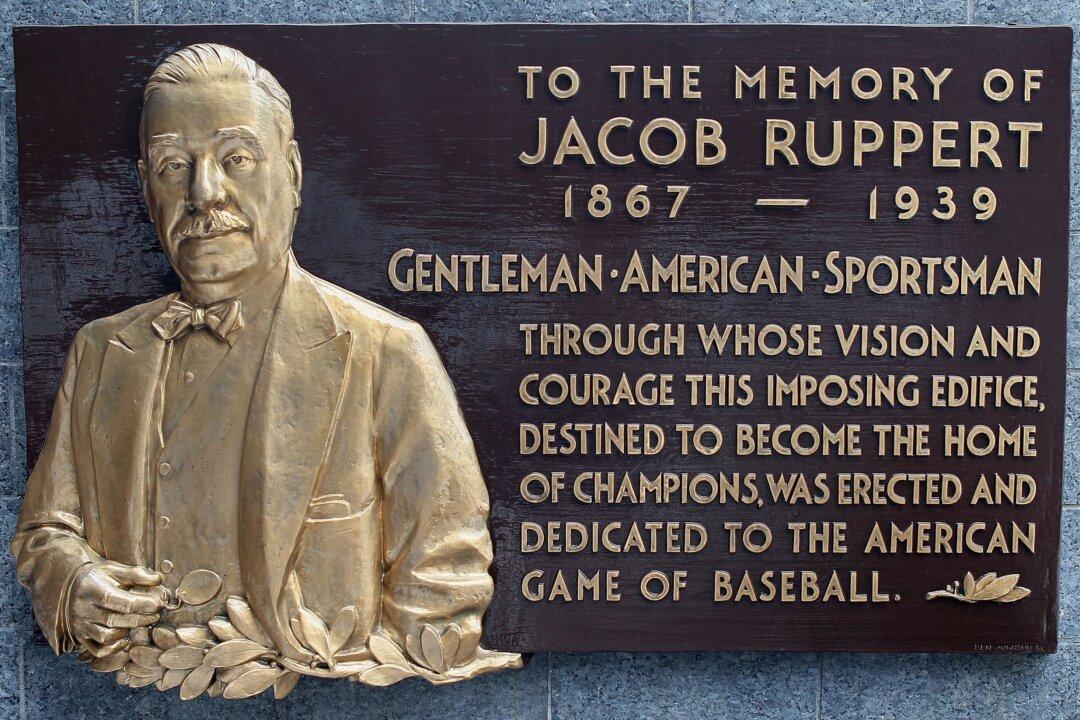

Those who voted saw fit to vote in this trio who lived long before the age of enhancement. One of the inductees was long overdue for admittance - Colonel Jacob Ruppert: the Man Who Built the Yankee Empire.

“It was an orphan club,” Ruppert said, “without a home of its own, without players of outstanding ability, without prestige.” It was a team whose average annual attendance was 345,000, and dozen year record was a mediocre 861 wins and 937 defeats. But Jake Ruppert, the man they would later call “Master Builder in Baseball,” would change all that.

On January 11, 1915, Jake Ruppert teamed with a real Colonel, Tillinghast L'Hommedieu Huston, and purchased the Yankees of New York for $460,000 from the original owners—professional gambler Frank Farrell and ex-police commissioner William S. Devery. Huston impressed everyone by peeling off 230 thousand dollar bills–his share of the purchase price.

Players and sportswriters referred to Hutson as “Cap.” There were others who called him “the Man in the Iron Hat” because of the derby hat, generally crumpled, that he wore. The hat matched his suits, always crumpled and rumpled.

A friend of Ruppert, “Cap” was a big bodied, self-made man who began his working career as a civil engineer in Cincinnati. A captain during the Spanish-American War, He made a fortune bringing the sewerage system and harbor of Cuba into the modern age.

The Farrell-Devery duo had milked and mismanaged the franchise for years. So owning the Yankees, who had a 12 year record of 861-937 and average attendance of 345,000 a season, would be a challenge for the new owners.

Ruppert and Huston, however, were up to the challenge. They had deep pockets and a great deal of business acumen and did they have connections. Huston was a successful entrepreneur engineer, a rich contractor. Ruppert always knew his way around a buck. Baseball beguiled both men; making money did, too.

All kinds of intrigue surrounded the purchase of the Yankees involving Tammany Hall wheeler dealers, other owners, and the American League President. All of them were very anxious to put in place new Yankee ownership and a successful franchise in New York City. To close the deal, American League owners and the League kicked in the rest of the half million dollars that Farrell and Devery insisted on before they would sell out.

“I never saw such a mixed up business in my life,” Ruppert complained right off the bat. “Contracts, liabilities, notes, obligations of all sorts. There were times when it looked so bad no man would want to put a penny into it. It is an orphan ball club without a home of its own, without players of outstanding ability, without prestige.”

All of that would change. The “Prince of Beer” wanted to re-name the Yankees to “Knickerbockers” after his best-selling beer, but the marketing ploy failed. Besides, it was said, the name was too long for newspaper headlines. Years later it would be short enough for basketball’s New York Knickerbockers.

Ruppert pressed on. As a beer baron, he was hands on for every aspect of his business. That same behavior pattern existed for him with the Yankees. He had a personal and deep interest in each player. He knew them all and was always up to date on their capabilities, shortcomings, foibles and performances.

In his early ownership years Ruppert lost almost as much money as was paid to purchase the Yankees. But on the field there was some progress. The team finished fifth in 1915, fourth in 1916, their first time out of the second division since 1910.

The Yankee owner rarely hung out with “with the boys,” Rud Rennie wrote in the New York Herald-Tribune. “For the most part, he was aloof and brusque.... He never used profanity. ‘By gad’ was his only expletive.”

A fixture at his Stadium, which he insisted on keeping so fanatically clean that sometimes he even swept it himself, Ruppert had a private box to which he invited the celebrities of the day. He was not an owner, though, who came to the park to be seen. His interest was in seeing his team, excel.

The Colonel’s idea of a wonderful day at the ball park was any time the Yankees scored 11 runs in the first inning, and then slowly pulled away. The Colonel was fond of saying, “There is no charity in baseball, I want to win every year.”

“Close games make me nervous.” he said. “A great day is when the Yankees score a lot of runs early and then just pull away.”

He created the “Ruppert effect.” Those who worked for him at the brewery or on the ball club knew he was around and about and very interested in all that was going on.

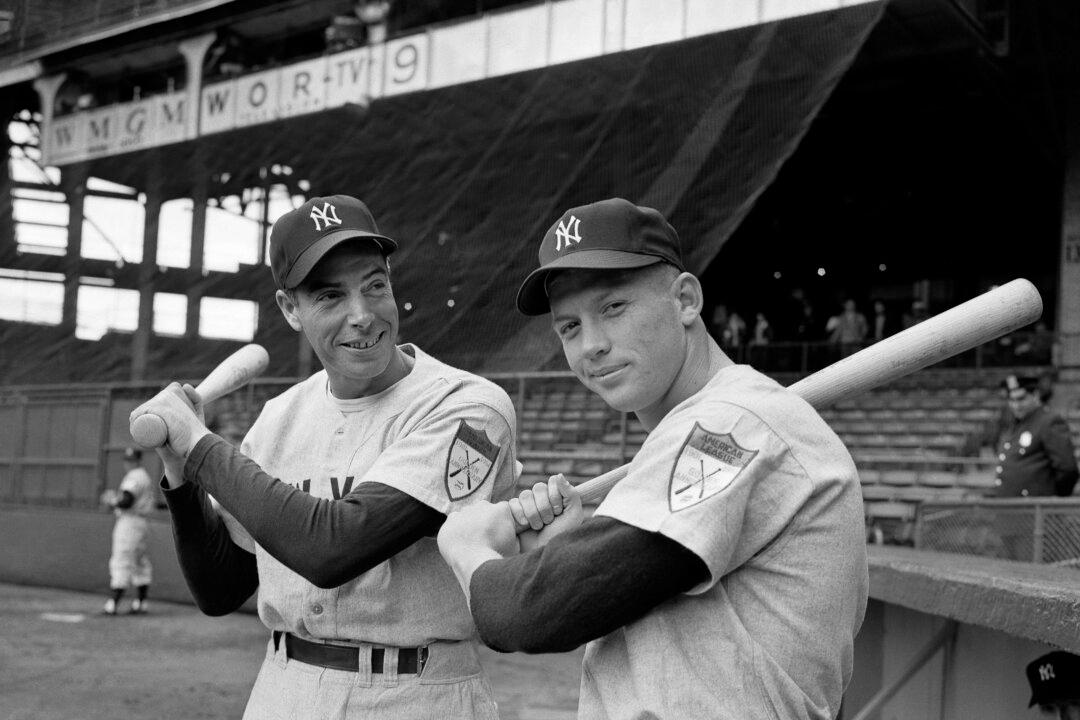

Members of his team received first class treatment. For the Yankees this showed itself in the sleeping accommodations he arranged on trains. Most other teams had players, dependent on seniority, given berths, upper or lower. The players on the New York Yankees all slept in upper births.

The whole traveling operation generally took up two cars at the end of the train. And there was many a summer day, that the players only wearing underwear (Babe Ruth, it was said, favored the silk kind), lolled about, had extended conversations, played cards, enjoyed each other’s company and the food, rest and recreation that made them perform better on the playing field.

While the Yankees were high flying, Ruppert’s other business – his brewery was hurting. Prohibition cut his brewery’s annual production of 1.25 million barrels of real beer to 350,000 barrels of half-percent near-beer that nobody wanted to drink. In effect, the brewery treaded water producing, bottling and selling “near beer”. Elected President of the United States Brewers Association in 1925. Ruppert led the battle to repeal Prohibition. Later, he was in the forefront in attempts to disassociate beer from saloons and promote its consumption in the home.

(To be continued)

A noted oral historian and sports journalist, the author of 41 sports books, including the classics “New York City Baseball 1947-1957,” “Shoeless Joe and Ragtime Baseball,” “Remembering Yankee Stadium,” and “Remembering Fenway Park,” is currently working on a book on the first Super Bowl—anyone with contacts, stories, suggestions please contact.