A-Rod suspended but still playing. The “House That Ruppert Built” demolished and the new Yankee Stadium built. What would Ruppert think? Who knows?

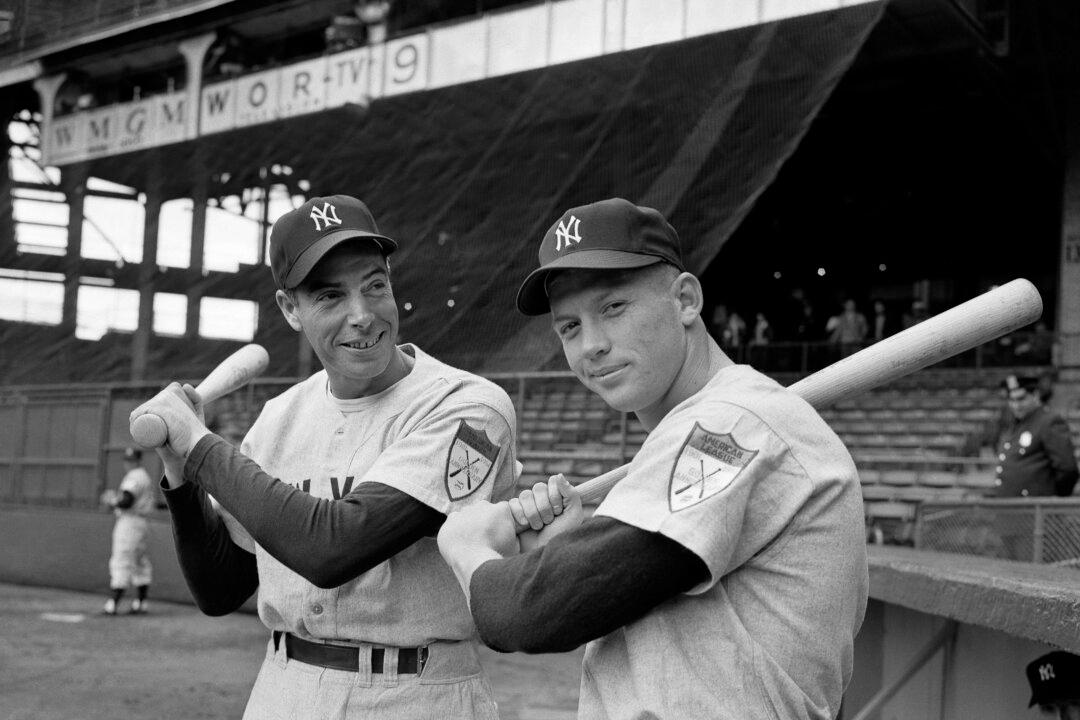

The old Colonel was a dreamer but also a doer, always making the moves. In a move that would change the course of Yankee and Red Sox history, indeed, baseball history, Jake Ruppert on January 3, 1920 purchased George Herman “Babe” Ruth, 25, from Boston. The deal was a very smart business move–the young Ruth had talent and would become one of the greatest drawing cards in baseball history. In his first season as a Yankee, he blasted 54 homers.

Ruth bragged “They’re coming out to see me in droves.” From 1920 to 1922, the Yankees with G.H. Ruth on board drew more three million fans into the Polo Grounds. Never had the New York Giants drawn a million fans in a season.

The Colonel was the only one to conduct salary negotiations with the “Sultan of Swat,” sometimes in the “Price of Beer’s” brewery office, sometimes in Florida when the Babe decided to hold out. George Herman Ruth was a valuable commodity and the Yankee owner treated him as such. The pair disagreed at times privately and publicly about contracts; nevertheless, Ruppert and Ruth were personal friends. Their relationship, though, could be described as love-hate.

Frugal to a fault, Colonel gave orders that the Yankee front office should always keep an eye out for any out of line Ruthian expenses. Thus, a $3.80 train ticket for Mrs. Ruth and a $30 “uniform deposit” were not honored for the greatest single gate attraction of all time.

Angered and annoyed at the gate success of Babe Ruth & Company, the Giants told the Yankees to look around for other baseball lodgings. The Yankees had been playing in the shadow of the Giants at the Polo Grounds since 1913, tenants of the National League team. It was a very unsatisfactory arrangement; now with the Yankees outdrawing the Giants in their in their own ballpark, it was an embarrassment.

The forward-looking Ruppert and Hutson suggested the Polo Grounds be demolished and replaced by a 100,000 seat stadium to be used by both teams and for other sporting events. The Giants were not interested. So the search was on to create a new ballpark, not just a new ballpark but the greatest and grandest edifice of its time, one shaped along the lines of the Roman Coliseum. The Colonel dreamed big dreams and had the power and money to back them up.

“The Yankee Stadium,” as it was called at the start, was envisioned as a structure that exuded a feeling of permanence. That was absent in earlier ballparks, like Fenway Park in Boston, Wrigley Field in Chicago, and Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Unlike the builders of older ballparks, Ruppert didn’t have to fit his park to the lines of city streets. Girth and height were there for the taking.

Public opinion in New York City was against the Yankees building a stadium. The government and the public claimed that there was a very severe housing shortage. It was felt that solving that problem was more important than building a new baseball park. “The Jake” did not care. He had his mind made up. He would find a place to build on.

Many sites and schemes were considered. One idea was to build a stadium or amphitheater over the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks along the West Side near 32nd Street. But the War Department nixed the idea. The space was reserved for anti-aircraft gun emplacements. The Hebrew Orphan Asylum, at Amsterdam Avenue and 137th Street, was a serious contender. A contract was actually drawn up, but the deal fell through. A lot in Long Island City in Queens was also given some consideration.

Finally, a site was selected, a former lumberyard in the west Bronx, City Plot 2106, Lot 100, a ten-acre mess of boulders and garbage. The cost for the land obtained from William Waldorf Astor’s estate and located directly across the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds, was $675,000—big money back then. One of the reasons the site was chosen by Ruppert was to irritate his former landlord. Another reason was that the IRT Jerome Avenue subway line snaked its way virtually atop the Stadium’s right-field wall and provided ease of transportation for fans.

Ruppert was criticized for his choice. The site was strewn with boulders and garbage. It was far from the center of New York City. Some dubbed the plan “Rupert’s Folly,” claiming that fans would never venture to a Bronx-based ballpark.

“They are going up to Goatville,” snapped John J. McGraw, manager of the Giants. “And before long they will be lost sight of. A New York team should be based on Manhattan Island.”

Ruppert never publicly responded to McGraw’s criticism. But he did ask all newspapers to provide the address of Yankee Stadium in all stories.

A millionaire many times over, Ruppert enjoyed giving orders and having them followed to the letter. Osborn Engineering Company of Cleveland, Ohio was charged with the design responsibilities. The White Construction Company of New York was given the construction job. The Colonel, a demanding taskmaster, insisted the ambitious project be completed “at a definite price” $2.5-million, be built in just 185 working days and be up and running by Opening Day 1923.

The Yankee owners dreamed the dream of a new ballpark, one along the lines of the Roman Coliseum. Some 500 men turned 45,000 barrels of cement into 35,000 cubic yards of concrete. Building bleachers out of 950,000 board feet of Pacific Coast fir that came to New York by boat through the Panama Canal, the concrete structure, with its massive triple-deck stands the first in baseball history, featured 60,000 seats, about the same as the Roman Coliseum had once boasted.

Some said the new baseball park should be named “Ruth Field” since it was built by and for Ruth—by his booming bat and iconic appeal. But Ruppert resisted. He wanted to have it named for his best-selling “Ruppert beer,” but that idea was resisted. So he insisted it be known as “The Yankee Stadium.” It would be the first ballpark to be referred to as a stadium.

On May 5, 1922, ground was broken for what would be the greatest and grandest edifice of its time, a structure shaped along the lines of the Roman Coliseum, Sixteen days later Ruppert would buy out Huston’s share of the Yankees for $1,500,000. “Cap” Huston had supervised all aspects of the building of Yankee Stadium from the selection of materials to quality and quantity of concrete used. Those talents, some said, were the reason Ruppert paired with him to buy the Yankees and build a ballpark.

On April 18, 1923, a massive crowd showed up for the proudest moment in the history of the South Bronx. It was Red Sox versus Yankees. Boston owner Harry Frazee walked on the field side-by-side with Yankee mogul Jake Ruppert. The teams followed the march beat of the Seventh Regiment Band, directed by John Phillip Sousa, to the centerfield flagpole, where the 1922 pennant and the American flag were hoisted.

Many in the huge assemblage wore heavy sweaters, coats and hats. Some sported dinner jackets. The announced attendance was 74,217, later changed to 60,000. More than 25,000 were turned away. They would linger outside in the cold listening to the sounds of music and the roar of the crowd inside the stadium.

It was one of Colonel Jacob Ruppert’s proudest moments.

“Yankee Stadium was a mistake, not mine, but the Giants,” was one of Ruppert’s favorite sayings.

(To be continued)

A noted oral historian and sports journalist, the author of 41 sports books, including the classics “New York City Baseball 1947-1957,” “Shoeless Joe and Ragtime Baseball,” “Remembering Yankee Stadium,” and “Remembering Fenway Park,” is currently working on a book on the first Super Bowl—anyone with contacts, stories, suggestions please contact.